Ever wished your horse had a speedometer? Good news! That technology may be just around the corner.

By training a software program to adjust data from inertial measurement units (IMUs) to horse-specific movements, Dutch and Swiss researchers have just created the first-ever equine speed and stride tracking system for all gaits.

The work promises an exciting new way to monitor horses for better performance, health, and welfare, scientists say.

You’ve got your running app that tells you how fast (or how slowly!) you ran that 5K last weekend. But try running around in an arena and see if you get the same results…

Now try riding your horse with it, and you’ll see that those global positioning system (GPS)-based tracking programs aren’t really designed for horses—and even less so if they’re working under a roof or around landscaping that blocks satellite signals.

Yet, knowing your horse’s speed has important advantages: you can monitor his conditioning; you can follow trends and see when something’s off; you can pace him more accurately for improved performance….

Because of all those reasons and more, equine scientists and engineers in The Netherlands and Switzerland teamed up to develop a reliable way to track horses’ speed—and their stride lengths—regardless of how fast the horse is going, what patterns he’s following, or whether he’s indoors or outdoors.

“In the current era of digitalization, we need more objective measurements than our subjective opinions, be it in competition, breeding, or veterinary lameness evaluations,” said Annik Gmel, PhD, of the Equine Department in the Vetsuisse Faculty of the University of Zurich and of Agroscope—Swiss National Stud Farm in Avenches, both in Switzerland.

“We (equine researchers) knew we needed a speed measurement linked to our other parameters of interest, but not being engineers, we couldn’t implement it alone,” said Gmel, who’s been collaborating for the past several years with Filipe Serra Bragança, DVM, a PhD candidate in equine musculoskeletal biology at Utrecht University’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Department of Equine Sciences, in The Netherlands.

“Being able to come together from different fields to adapt systems for practical applications has been deeply rewarding.”

Hamed Darbandi, PhD, of the Pervasive Systems Group in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Twente, in Enschede, The Netherlands, comes from one of those “different fields.” And he was eager to get on board the project.

“Why do many people wear smartwatches?” Darbandi said. “It’s because they want to track their activity, right? I think that is also the case for horses. Not all horses are athletic horses, but tracking their activity can be beneficial for their health.”

So Darbandi, Serra Bragança, Gmel, and their fellow researchers took advantage of data from other ongoing gait analysis studies in which researchers had equipped 15 Icelandic horses and 25 Franches-Montagnes with a double gait-tracking system using both GPS (Global Positioning System) and IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) technology.

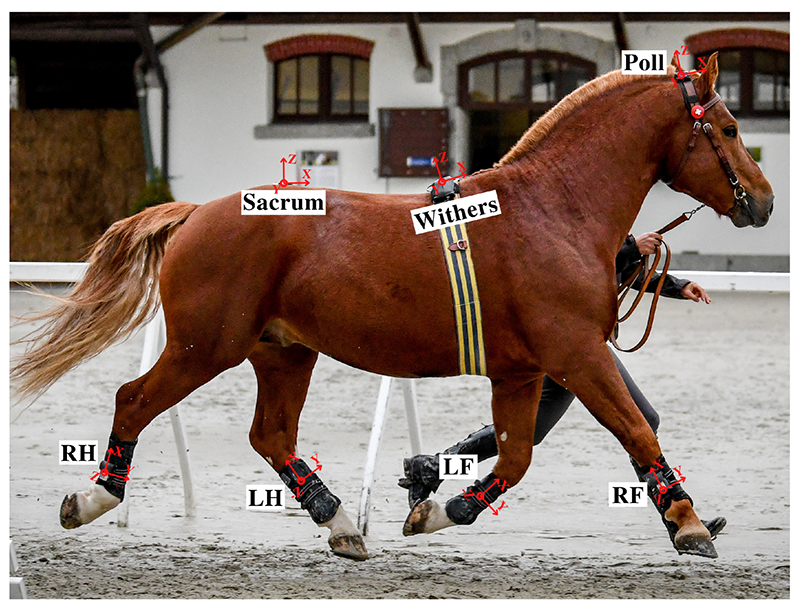

The horses wore seven IMUs placed one each at each leg, the poll, the withers, and the sacrum, as well as one GPS module at either the withers or the sacrum.

Locations and orientation of inertial measurement units (IMUs) on the horse’s body. RF: right front limb, LF: left front limb, RH: right hindlimb, LH: left hindlimb. Photographed by Christelle Althaus.

The horses were worked at walk, trot, tölt, pace, and/or canter, in hand or under saddle, outdoors, with good satellite signal.

The computer engineers then developed a software model that could convert the IMU data into accurate speed determination—as determined by the GPS data which, having been collected outdoors, was considered a reliable standard.

It took some time, requiring the engineers to correct the software and teach it to adapt the data to the particular way horses move in each gait.

Through all this machine learning, though, the scientists finally achieved an accurate, working model that consistently calculated the horses’ actual speeds, using the IMU data alone. In fact, they were even able to get the model to estimate speed correctly using a single IMU on the body or a leg, meaning the horse would only need to wear one IMU instead of the seven used in the study.

“The results of our study show that speed can accurately be estimated independent of the environment,” Darbandi said.

This technological development could soon allow horse people to be equipped with more objective information as they make decisions regarding performance, training, and even breeding, according to Gmel.

“For our research project—Shape and Gaits 2.0—we use the system to measure the movement of horses to quantify what a good walk, trot, or canter is, objectively speaking, so that we can improve the selection of horses for breeding,” she told Horses and People.

“As we know from previous experiments, speed has an effect on many measures of interest, and horses adapt to speed changes in different ways. For example, we are interested in whether the horse increases stride length or stride frequency with higher speeds, as this will make the difference between a real extended trot and a hurried trot without scope in dressage.

“For performance, we want to select the horses with longer strides and lower frequency,” she continued. “But for a fair comparison between horses, we need to match the stride length and frequency with individual speeds, which we can now measure thanks to [Darbandi’s] method.”

According to Darbandi, currently, the speed estimator only works through the software program and can’t work in real-time like a speedometer. But such a device might be just around the corner.

“It can be simply modified to a live version, which can report the speed value to the rider live and in a second!” he said. A future version could easily also include a heart rate monitor for real-time cardiac monitoring, he added.

“As time goes by, we can see that more and more riders, veterinarians, and coaches are becoming more sophisticated about the impact of technology on horse health and performance,” said Darbandi.

“We hope that other scientists will contribute to spreading the benefits of using technology for equine health and performance, and that more riders will accept it as a tool to help their horses more than before.”