Bits and their impacts on horses have been receiving increasing attention of late. Key issues considered are the purposes of their use, the design-related impacts on different mouth parts, how they are used, and finally, negotiating the intersection between the human-focussed purposes of their use and the impacts of that on the horse. My aim here is not to cover all these matters, but enough of them to allow me to share my views in the perfect bit.

Why Bits are Used

Horses are powerful and versatile animals which, when trained, have historically performed diverse functions, including those that lead to practical, economic, political, military, social, spiritual and recreational benefits for the persons who own them or have charge of them [1].

However, horses do not volunteer for these roles; rather they are coercively recruited, trained and subdued to comply with the wide range of human focussed demands on them. The principal means for achieving these objectives is the use of bits strapped into the horses’ mouths and manipulated with hand-held reins. Other varieties of tack are used to reinforce the efficacy of bit use.

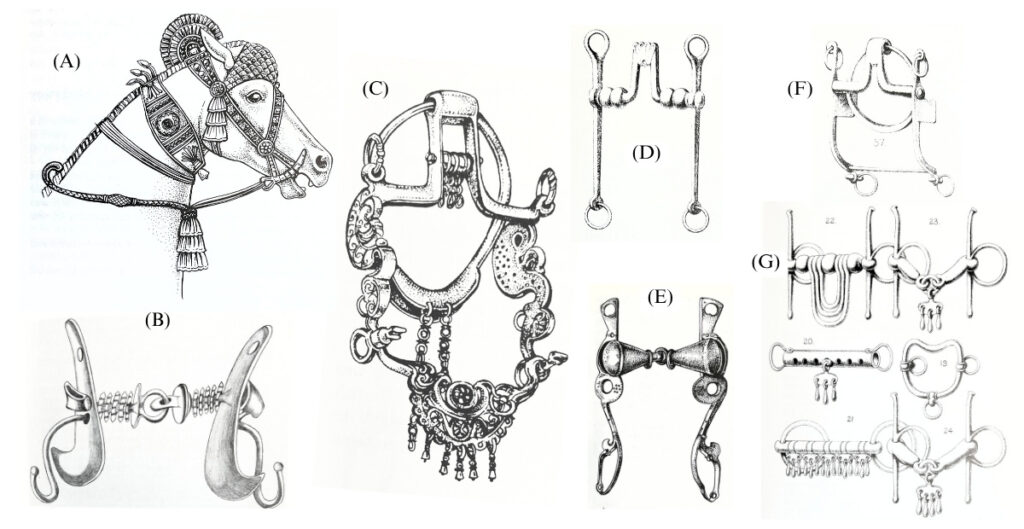

Figure 1. Despite frequent references in horsemanship writings to gentle methods and soft bits, the archaeological and historical record tells a different story. Shown here are examples of bits that were anything but gentle: (A) an Assyrian bridle (c. 12th century BC); (B) a Greek jointed snaffle with a spiked mouthpiece, recommended by Xenophon (430–355 BC) as an alternative to a softer bit; (C, F) North African ring bits, used since Roman times and still in use today. (D) The Celts of Gaul (4th century BC) invented the levered curb bit with curb chain; (E) a European canon curb bit from the Middle Ages; and (G) late-19th-century contrivances to prevent horses placing their tongues over the bit, described in The Loriner by Benjamin Latchford (1883). Illustrations from E. Hartley Edwards, Bitting in Theory and Practice (J. A. Allen).

Mouth-Bit Interactions

The internal structures of the mouth, including the gums, bars, tongue, teeth, hard and soft palate, larynx and inner mucosae of the cheeks are exquisitely sensitive to touch. This is essential to enable the horse to manipulate herbivorous food materials for swallowing and to expel foreign objects like stones. The lips also have high tactile sensitivity to enable selective nibbling and focussed incisor-biting of edible material, which is then taken into the mouth.

The tactile sensitivity of these mouthparts is matches by their exquisite sensitivity to pain, in particular, the gums, bars, tongue and teeth. Metal bits, or at least bits made of solid materials, when is contact with these tissues stimulate pain receptors, such that the greater the pressure, the worse is the experience of pain. Note however that high intensities of pain in sensitive oral tissues, e.g., the gums, can be caused by very low levels rein-induced bit pressure that do not cause tissue damage.

The Mellor Pen Test

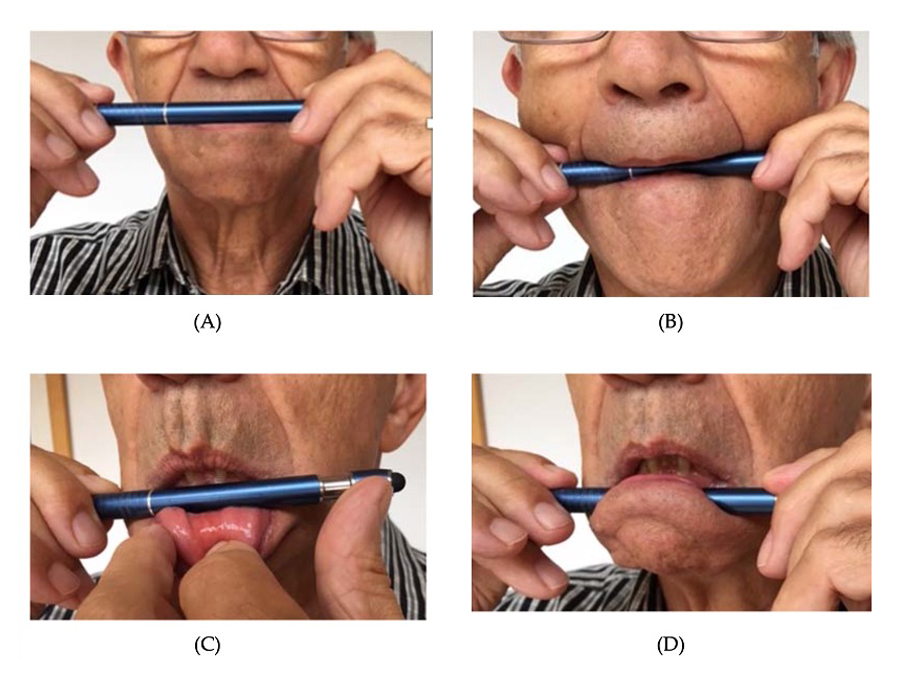

Readers may gain a personal insight into the likely intensity of such pain by conducting on themselves what has come to be known as the “Mellor pen-test” [2]. This test is intended to simulate the compressive effects of bit pressure applied to the gums lining the interdental space (the bars) of a horse. It involves applying pressure to the barrel of a pen placed against the gums below the front incisor teeth of the lower jaw (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The ‘Mellor pen test”, reproduced with permission from the author who holds the copyright [2]. This simulates bit pressure applied to the gums of the interdental space of the horse. Gums are exquisitely sensitive to painful stimuli, including compression. Rein tension transferred to the bit in contact with the gums of the interdental space causes pain. (A) Position 1: Hold the pen in front of your mouth; (B) Position 2: Open your mouth, place the pen where the upper and lower lips meet on each side, and then push the pen towards the back of your throat. No gum contact, no significant pain; (C) Position 3a: Roll your bottom lip down and locate the pen on the gum, below your central incisors; (D) Position 3b: Now release your lip and with both hands holding the pen, apply compressive pressure to your gum, carefully increasing the pressure in steps from very low until the pain is too intense to continue. How much compression-induced pain could you stand?

In common with the experiences of audiences totalling at least 450 addressed by the author prior to the publication date of the ‘test’ in 2020 [2], and numerous others who tested themselves during the intervening period, it is anticipated that the vast majority of readers will find that intense pain may be generated by low pressures, and well before any tissue damage occurs. This also makes it clear that pain, even severe pain can occur without causing observable lesions. However, bit-induced traumatic injuries to all pain-sensitive oral tissues including the gums of the interdental space (bars), the tongue, teeth, cheeks and lips are fairly common [e.g., 2-14].

Bit Design, Rein Pressures and Mouth Pain

There are numerous bit designs. Whatever their specific features are, any contact of bit parts with pain-sensitive oral tissues will cause pain, and this at commonly observed rein pressures quantified in well conducted bona fide studies [e.g., 15-22]. The rein pressures that equestrians directly experience in their hands as low or light, often underestimate the mouth-pain impact on the horse. This underestimation is likely to be most prevalent when curb bits are used because of the magnifying effects of the shank and chain. This is well recognised by those with a smattering of elementary physics and has been explained and graphically illustrated recently [23].

Bit-induced Mouth Pain and Behaviour

Additional unequivocal behavioural evidence that bits cause mouth pain has been derived from: (1) extensive published observations of the behaviour of bitted horses compared with the same horses bit-free, i.e., wearing halters or no bridle; (2) that of domesticated horses being ridden or driven bit-free; and (3) extensive video records of freely ranging bit-free wild horses from Australia, France, New Zealand and the USA (Mellor 2020). More recently (mid-2025), striking photographic behavioural evidence clearly indicating bit-induced mouth pain in dressage horses was provided in a submission to the Veterinary Committee of the FEI (Fédération Équestre Internationale) [24].

The Perfect Bit?

The perfect bit from a horse-centered welfare perspective is one, attached to a bridle or not … that is never removed from its hook on the tack room wall!

References

- Fraser, D. Understanding Animal Welfare: The Science in its Cultural Context; Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK. 2008.

- Mellor, D.J. Mouth pain in horses: Physiological foundations, behavioural indices, welfare implications and a suggested solution. Animals 2020, 10(4), 572; https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10040572

- Cook, W.R. Bit-induced pain: A cause of fear, flight, and facial neuralgia in the horse. Pferdeheilkunde 2003,19, 75–82.

- Cook, W.R.; Strasser, H. Harmful effects of the bit. In Metal in the Mouth: The Abusive Effects of Bitted Bridles; Kells, S., Ed.; Sabine Kells: Qualicum Beach, BC, Canada, 2003; pp. 3–13, ISBN-10: 0-9685988-5-4, ISBN-13: 978-0-9685988-5-6.

- Cook, W.R. Damage by the bit to the equine interdental space and second lower premolar. Equine Vet. Educ. 2011, 23, 355–360, doi:10.1111/j.20423292.2010.00167.x

- van Lancker, S.; van den Broeck, W.; Simoens, P. Incidence and morphology of bone irregularities of the equine interdental space (bars of the mouth). Equine Vet. Educ. 2007, 19, 103–106

- Bendrey, R. New methods for the identification of evidence for bitting on horse remains from archaeological sites. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 1036–1050

- Mata, F.; Johnson, C.; Bishop, C. A cross-sectional epidemiological study of prevalence and severity of bit-induced oral trauma in polo ponies and race horses. J. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2015, 18, 259–268, doi:10.1080/10888705.2015.1004407.

- Johnson, T.J. Surgical removal of mandibular periostitis bone spurs caused by bit damage. Am. Assoc. Equine Pract. 2002, 48, 458–462.

- Tuomola, K.; Maki-Kinnia, N.; Kujala-Wirth, M.; Mykkanen, A.; Valros, A. Oral lesions in the bit area in Finnish trotters after a race: Lesion evaluation, scoring and occurrence. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 206, https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00206.

- Bjornsdóttir, S.; Frey. R.; Kristjansson, T.; Lundstrom, T. Bit-related lesions in Icelandic competition horses. Acta Vet. Scand. 2014, 56, 40. Available online: http://www.actavetscand.com/content/56/1/40.

- Equus 2019. Tongue Injuries: Wounds to Your Horse’s Tongue Can Easily Go Unnoticed—But That Doesn’t Mean They Can be Ignored https://equusmagazine.com/horse-care/tongue-injuries-12258 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Tell, A.; Egenvall, A.; Lundstrom, T.; Wattle, O. The prevalence of oral ulceration in Swedish horses when ridden with bit and bridle and when unridden. J. 2008, 178, 405–410

- Uldahl, M.; Clayton, H. Lesions associated with the use of bits, nosebands, spurs and whips in Danish competition horses. Equine Vet. Educ. 2018, 51,154–162, doi:10.1111/evj.12827.

- Clayton, H.M.; Singleton, W.H.; Lanovaz, J.; Cloud, G.L. Measurement of rein tension during horseback riding using strain gage transducers. Tech. 2003, 27, 34–36.

- Clayton, H.M.; Larson, B.; Kaiser, L.A.J.; Lavagnino, M. Length and elasticity of side reins affect rein tension at trot. J. 2011, 188, 291–294.

- Egenvall, A.; Eisersiö, M.; Rhodin, M.; van Weeren, R.; Roepstorff, L. Rein tension during canter. Exerc. Physiol. 2015, 11, 107–117.

- Egenvall, A.; Roepstorff, L.; Eisersiö, M.; Rhodin, M.; van Weeren, R. Stride-related rein tension patterns in walk and trot in the ridden horse. Acta Vet. Scand. 2015, 57, 89.

- Egenvall, A.; Clayton, H.M.; Eisersiö, M.; Roepstorff, L.; Byström, A. Rein tensions in transitions and halts during equestrian dressage training. Animals 2019, 9, 712.

- Piccolo, L.; Kienapfel, K. Voluntary rein tension in horses when moving unridden in a dressage frame compared with ridden tests in the same horses—A pilot study. Animals 2019, 9, 321.

- Heleski, C.R.; McGreevy, P.D.; Kaiser, L.J.; Lavagnino, M.; Tans, E.; Bello, N.; Clayton, H.M. Effects on behaviour and rein tension on horses ridden with or without martingales and rein inserts. J. 2009, 181, 56–62.

- Christensen, J.W.; Zharkikh, T.L.; Antoine, A.; Malmkvist, J. Rein tension acceptance in young horses in a voluntary test situation. Equine Vet. J. 2011, 43, 223–228.

- Uldahl, M. and Mellor, D.J. Regulatory Integrity and Welfare in Horse Sport: A Constructively Critical Perspective. Animals 2025 15, 1934. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131934

- Wilkins, C.; Henshall, C.; McGreevy, P.; Mellor, D.; Tuomola, K.; Parellius Johannessen, C.; Lykins, A. Welfare in Dressage: Visual and Scientific Evidence. A 50-Minute Briefing Entitled “Equipment-Induced Pressures Affecting Sport Horses. Evidence and Welfare Impacts” Delivered to the FEI Veterinary Committee on 9 April 2025. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W6OgVEC4i28 (accessed on 18 August 2025).