This final paper by the late Dr William Robert “Bob” Cook (1931–2025) brings together a lifetime of research and advocacy for horses’ welfare. In his last days, Dr Cook entrusted this work to Horses and People, wishing it to stand as the culmination of his efforts to “unshackle the horse.” His family shared that he was overjoyed to know it would be published.

For more than fifty years, Dr Cook challenged long-standing equestrian traditions with evidence that bits harm horses and bit-free riding improves comfort, performance, and safety. It is published here in tribute to a scientist, teacher, and advocate whose compassion and persistence continue to shape the future of horse welfare.

“The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their right names.” Chinese Proverb

The age of a sport born in the Iron Age is measured in centuries. With a bit-free option added to the rules, horses will be emancipated, and horse sports could celebrate a ‘coming of age’ in the 21st century.

Article Highlights:

- Evidence published since 1988 indicates that the bit method of rider/horse communication causes mouth pain, many diseases, and seriously impedes a horse’s ability to breathe at fast exercise.

- Bit-induced pain and suffocation in the racehorse is the cause of bleeding from the lung, catastrophic accidents, and sudden death; events that jeopardize horseracing’s social license to operate. Bit-ridden racehorses become ‘lame in the lungs’, disabled physically, and disturbed mentally. Negative effective mental states are intensified (Mellor et al 2020), and peak performance is prevented.

- In all competitive sports, and in recreational riding, the use of one or more bits causes pain, disease, and injury; hampering breathing, handicapping performance, and increasing the risk of accidents. In recreational riding, by comparing bit-ridden with bit-free performance, the bit has been shown to cause 69 pain-induced conflict behaviors (Cook and Kibler 2018).

ABSTRACT

The anatomy and physiology of the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract was studied with particular attention to pathophysiology and pathology brought about by use of the bit (Cook 1998a, b, 1999a, 2001a, c, 2003a).

A survey was carried out of Equus caballus skulls in USA National History Museums for the prevalence of bit-induced damage to the interdental space and the second lower premolar (Cook 2011).

Behavioral studies were conducted to compare performance with and without the bit (Cook and Mills 209, Cook and Kibler 2018, 2022).

In eventing and racing (and because peak performance is the target and bit-use mandatory), bit-induced conflict (i.e., defensive) behaviors are more frequent and severe. Suffocation triggers a cascade of severe chest pain, waterlogging and bleeding of the lungs (negative pressure pulmonary edema), a sense of drowning, existential fear, physical exhaustion, stumbling, falls, catastrophic accidents, and sudden death.

Collectively, the number of bit-induced diseases, disorders, discomforts, and disasters is close to 100. Bit-induced pain and fear are incompatible with Learning Theory and the spirit of an activity called sport.

Bit-free trials are recommended for all disciplines. The evidence predicts that trial results will confirm the benefits of a bit-free option.

Bit-free Sport: Predicted Benefits

Bit-free sport will:

- Improve the quality of life for horses.

- Improve performance and set new records.

- Reduce accidents and injuries to horses, riders, and handlers.

- Increase a horse’s value.

- Reduce maintenance costs.

- Foster the general public’s support for horseracing and the betting public’s interest.

- Solve the shortage of equine veterinarians.

- Sustain Horse Sports’ Social License to Operate.

Keywords: Bit-induced pain, pathophysiology, pathology, aberrant behavior, poor performance, sudden death.

INTRODUCTION

The horse’s mouth: A sensory and survival-critical organ, not a control device

The horse’s whiskered muzzle and mouth is a sensory probe that enables horses to feel their way around the world and fastidiously select what they put in their mouth. The horse is a nose-breathing animal, and the mouth is the guardian of the respiratory tract. Unless the mouth is closed and the lips are sealed, a fast-running horse suffocates.

Regrettably, riders and drivers are required by most competition rules to use a bit, an Iron-Age invention that breaks the lip seal, handicaps a horse’s ability to breathe, causes pain, a multitude of behavioral side-effects and unintended consequences. Ironically, the mouth-iron method of communication is the most common cause of complete loss of control.

What evidence shows about performance

Would you like to improve your dressage score from 37% to 64%? This was the average improvement that riders of four mature school horses achieved in their bit-free trial at the 2006 Annual Conference of the Central Horsemanship Association (Cook and Mills 2010).

In the bit-ridden racehorse, a toxic combination of mouth pain, suffocation, pulmonary edema, bleeding from the lung, chest pain, a sense of drowning, fear, and physical exhaustion is the probable cause of stumbling, falls, catastrophic accidents, and sudden death (Cook 2022a, b, c). Mandatory-bit rules prevent the superiority of bit-free performance from being brought to light. Significantly, in 25 years of bit-free recreational riding (2000-2025), no accidents or deaths have been reported.

The myth of control

To summarize, the mouth-iron method is dangerous and inhumane. The belief that “a bit controls” is a myth. A fundamental flaw of the method is that, at any moment, the horse can choose to take control. Shakespeare (1593) summed it up succinctly:

“The iron bit he crusheth ‘tween his teeth, controlling that by which he was controlled.”

Bit-ridden horses, nervous and highly-strung because of mouth pain, are more likely than bit-free horses to spook, toss their heads, buck, rear, bolt, or freeze at the foot of a jump and dislodge their riders.

Bit-free, a previously nervous bit-ridden horse becomes calm, confident, and compliant. Bit-free is pain-free, safer and more enjoyable for horses and riders. Bit-free sport will become more popular with the public and horse sports’ social license to operate will be supported.

Historical voices against the bit

Horses have a highly developed sense of touch. They can feel a fly landing anywhere on their body. Their lips are an especially sensitive part of their skin, and their tongue is another sense organ. The ‘bars’ of a horse’s mouth are two knife edges of bone, with a sensitivity far greater than that of the human shin.

I call as a witness William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle. In his 1657 classic “The New Method of Dressing Horses” he wrote:

“It is not a piece of iron can make a horse knowing, for if it were, the bitt-makers would be the best horsemen: no, it is the art of appropriate lessons … and not trusting to an ignorant piece of iron called a bitt, for I will undertake to make a perfect horse with a cavesson without a bitt, better than any man shall with his bitt without a cavesson; so highly is the cavesson, when rightly used, to be esteemed. I dressed a barb at Antwerp with a cavesson without a bitt, and he went perfectly well; and that is the true art, and not the ignorance and folly of a strange-figured bitt.”

In her book “The Horses Who Made Me: A Journey to a Horsemanship Philosophy”, Alizée Froment (2024) describes how, after a career in Five Star FEI Dressage, she transitioned her horses to bit-free and demonstrated Liberty Performances around the world. Dressage is an exacting test of control. Froment sets an example for other disciplines to follow.

Modern reformers and missed opportunities

In 2024, the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA) sponsored a global summit in Toronto, the purpose of which was to improve racehorse safety and highlight steps for reducing the incidence of catastrophic accidents and sudden death. Presentations at the meeting have been published and are freely accessible in the Equine Veterinary Journal’s “Online Collection” at https://beva.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/evj.14432.

Some years ago, the IFHA recommended the Five Domains Model (Mellor et al 2020), as the standard for equine welfare assessment. Though the IFHA Global Summit was convened expressly to explore how racehorse welfare might be improved, application of the Five Domains Model and studies on mouth pain by Mellor and Beausoleil (2017a, b), Mellor (2019a), Mellor and others (2020), were not highlighted. Since then, attention has been drawn to the need for “Translating Ethical Principles into Law, Regulations and Workable Animal Welfare Practices.” (Mellor and Udahl 2025).

“The belief that ‘a bit controls’ is a myth.”

As judged by 22 articles listed as relevant to the Global Summit in the Equine Veterinary Journal (JVB) Online Collection (2024), the welfare topic of bit-inflicted pain and asphyxia was not discussed.

An atypical hotlink in the reference to Lyle et al, 2011 reads, “See also correspondence by Cook.” When followed, this did not lead to correspondence but to four more hotlinks; Lyle et al (2011), Cook (2015), Uldahl and Clayton (2018), Cook and Kibler (2018). The second of these had the relevant title “Bit-induced asphyxia in the racehorse as a cause of sudden death.” Another article of relevance that could have been listed was Cook (2013).

Noticeable also by its absence was the lack of any reference to the Five Domains Model for the assessment of animal welfare (Mellor et al 2020). As the IFHA recommends the Five Domains Model as the standard method for welfare assessment, this omission is difficult to understand in an IFHA-sponsored Global Summit on racehorse welfare.

Comparing forces applied: Bits and nosebands

Currently, much attention is being focused on the amount of pressure that tight nosebands in dressage horses exert on the nasal bone at the bridge of the nose (Hopkins et al 2025). The pressure was considered significant and shortened a horse’s stride. The pressure of a bit on the bars of the mouth, a far more sensitive and smaller contact area, has not been measured.

The purpose of this article is to draw attention to the bit; an item that radically undermines the safety and welfare of racehorses and all bit-ridden horses.

THE MOUTH-IRON’S IMPACT ON THE HORSE

From food source to weapon of war

1. In prehistoric times it was recognized that the horse (unlike the zebra) was suitable to be ridden; enabling mankind to make use of the horse’s physical ability, strength, and speed.

2. The nature of horses is such that they will work for us if, at the very least, two conditions are met. That the partnership is pain-free and does not interfere with their ability to breathe.

3. Unfortunately, the bit-ridden horse became a weapon of war. Warfare, not welfare, was the objective.

From the Iron Age to Modern Sport

4. The bit caused pain, suffocation, and negative affective mental states (Mellor and Beausoleil 2017a, b, Mellor et al 2020).

5. Early bits were made from wood or antler that could be bitten through and broken.

6. With the development of metallurgy skills in the Iron Age, mouth-metal became customary (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An Iron Age bit, modelled by a terracotta horse. One of 520 chariot horses in the ‘Terracotta Army’ Mausoleum of the first Emperor of China 210-209 BCE. Dreamstime.com

7. An internet search for ‘images of iron age bits’ revealed a profusion of designs; an inventiveness that has continued to the present day. When so many solutions are suggested for the same problem, we are alerted to the possibility that none are entirely satisfactory.

8. Horseracing traces its origins back to 4500 BC (IFHA, Horse Integrity Handbook, 2024).

9. In the 19th century, when formal rules for racing and other horse sports were first drawn up, though the mouth-iron method of communication had not been validated by testing, bit use was ‘grandfathered-in’ without question and made mandatory.

10. The method was eventually questioned on the grounds that it caused pain, suffocation and was a seriously flawed method of communication (Cook 1998 a, b, 1999 a, b, c, and 2000-2024).

Scientific evidence of harm

11. Independent evidence of the bit’s harm to equine welfare was contributed by the analyses of Beausoleil and Mellor (2015), Mellor and Beausoleil (2017a, b), Mellor (2017), Mellor (2019 a, b), Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones, and Wilkins (2020), Mellor and Uldahl (2025), Uldahl and Mellor 2025, and by Mellor under his pen name Garnham (2024 a, b, c, 2025.)

12. In addition to assessing the effect of four other items on the welfare of the horse, the Five Domains Model (Mellor et al 2020) assesses the bit’s effect on the mental state of the horse. Thoroughbred Racing New Zealand was the first to adopt it as their standard, followed quickly by other national racing authorities, and by the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA). The Five Domains Model, a landmark advance for the assessment of equine welfare, drew attention to the need to consider negative affective mental states caused by the bit. It is to be hoped that following the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI), the International Horse Sports Confederation (IHSC), and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) will also adopt the Five Domains Model.

13. In January 2022, an influential book was published with the title “I Can’t Watch Anymore” and the arresting subtitle “The Case for Dropping Equestrian from the Olympic Games. An open letter to the IOC.” (Taylor 2022).

14. Today, many riders have recognized that the bit is an invasive, painful, and suffocating foreign body in the mouth of a powerful and easily frightened prey animal. Nevertheless, mouth-irons remain mandatory for racing and FEI Endurance, Eventing, and Dressage, though not for Show Jumping. The Netherlands, Denmark, Hungary, and Kenya have led the way by allowing bit-free dressage at all levels short of Grand Prix.

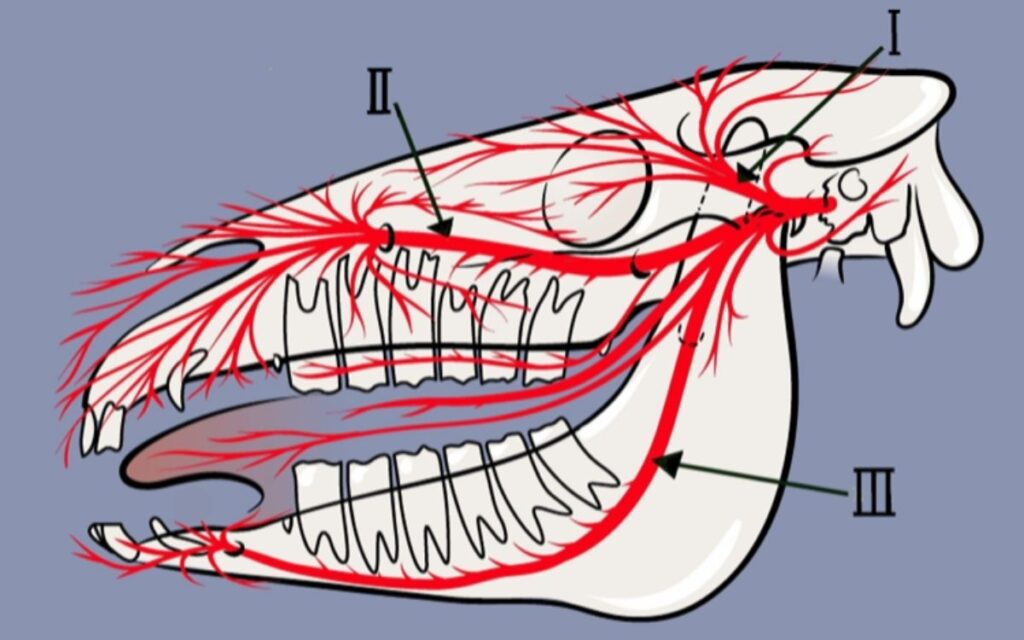

15. The Trigeminal nerve provides sensation to the whole of the head (Figure 2). It is a nerve of particular significance in relation to bit usage because of its function as a transmitter of touch and pain signals from the horse’s sensory probe (muzzle, lips and chin) to the brain and beyond to affect multiple body systems.

Figure 2. The 3 branches of the Trigeminal nerve: sensory to the eye (I), upper jaw (II), and lower jaw (III) with the bit in the ‘tongue-over-bit’ position. Bit-induced trigeminal neuralgia in the horse, the common and severely painful disease of ‘headshaking’, can be career-ending for a dressage horse.

16. The presence in the horse of a trigemino-cardiac reflex (Chowdhury and Schaller 2015) has been overlooked as a possible cause of sudden death from cardiac arrest in the racehorse.

Ethics, Learning Theory, and the spirit of sport

17. The mandatory infliction of pain in horse sport is ethically unacceptable, incompatible with the principles of Learning Theory, and the spirit of an activity called sport. Use of the bit jeopardizes the welfare of both horse and rider. Bit-free communication is possible, more likely to be pain-free, does not precipitate aversive behavior, and allows a horse to breathe freely.

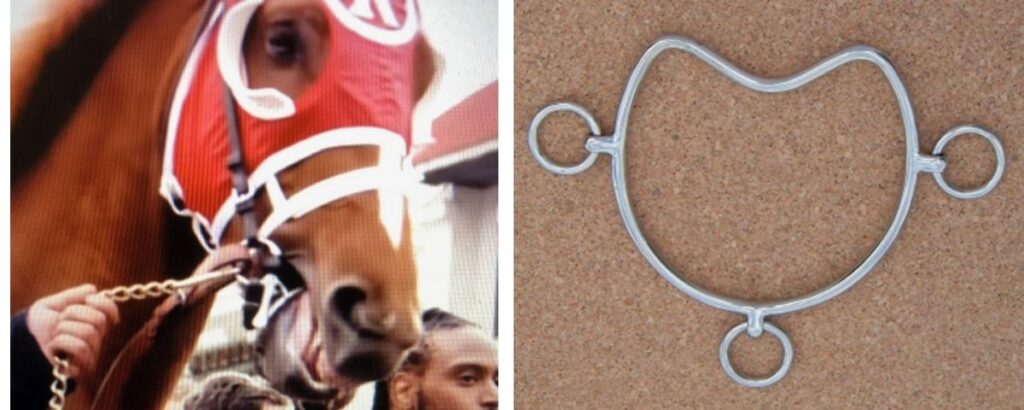

18. Thoroughbred racehorses are often encumbered with two bits (the Dexter Ring Bit; a snaffle and a ring bit – Figure 9). A driving bit is mandatory for Standardbreds in Harness Racing, and two bits are present when an overcheck bit is added.

19. In recent decades, the bizarre practice of tying a racehorse’s tongue to the lower jaw – read here, and here – has been allowed in the mistaken belief that it prevents ‘swallowing of the tongue’, i.e., dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) and strangulation.

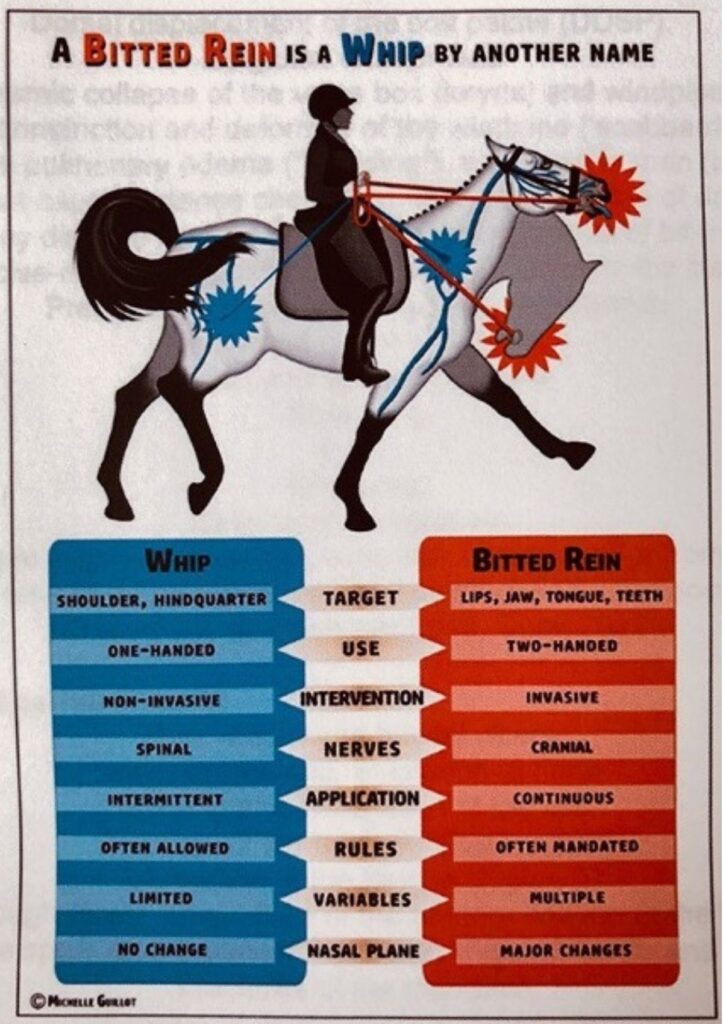

20. More recently, the public has expressed concern about the use of whips. A bit-armed rein is a mouth whip (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A bitted rein is a whip by another name. Illustration by Michelle Guillot.

How the bit obstructs breathing

21. A fundamental goal of dressage is ‘acceptance of the bit.’ Acceptance by the horse of a foreign body in the mouth is an unrealistic expectation, arising from a failure to recognize fundamental facts about the physiology of the horse. Horses in the wild run with a closed mouth, a relatively dry mouth, sealed lips, a negative pressure in the oral cavity and, depending on speed, varying degrees of head/neck extension (Figure 4). At liberty, horses instinctively reject anything in their mouth other than food or water.

Figure 4. A horse running at liberty with a closed mouth and sealed lips. The elliptical shadow posterior to the corner of the mouth is a dimple at the level of the interdental space (‘bars’ of the mouth) that marks the negative pressure (vacuum) in the oral cavity; essential for enabling the nose-breathing horse to breathe freely at exercise. The straight edge of the dimple marks the roof of the mouth (hard palate). The vacuum clamps the soft palate to the root of the tongue and voice-box, preventing it from elevating during each inspiration and obstructing the airway when running (see diagrams at Cook 2024a). A good time to observe the dimple is when a horse is drinking; another activity dependent on negative pressure in the oral cavity. A bit-ridden endurance horse can be reluctant to drink because of mouth pain, and unable to drink because a bit breaks the lip seal and prevents the creation of negative pressure. Image Dreamstime.com.

Horses quickly develop many ways to negate bit-induced pain. None of the defensive behaviors are ‘acceptable’ to the rider. All of them distract the horse’s attention from complying with the rider’s signal. Some behaviors (e.g., bolting, bucking, and rearing) endanger the life of the horse and rider. Apart from the pain of a bit-armed rein, a mouth-iron is an aversive and pathophysiological foreign body in a horse’s mouth. For dressage, a double bridle (two bits) was mandatory until quite recently when, in some countries, a single, non-leverage bit became optional in some classes.

22. A 50-minute video briefing entitled “Equipment-Induced Pressures Affecting Sport Horses. Evidence and Welfare Impacts” provides textual and visual evidence of bridle pain in dressage horses (Wilkins, C, Henshall, C, McGreevy, P, Mellor, D.J, Tuomola, K, Johannessen, C.P, Lykins, A 2025). The briefing was delivered to the FEI Veterinary Committee on 9 April 2025 and is available online.

23. With the unavailing purpose of trying to prevent dressage horses from responding to bit-induced pain by opening their mouth, crank-nosebands became an ineffective custom and a further cause of pain. In dressage, the mouth-metal method causes ‘riding behind the vertical’, and obstruction of the airway. Similarly, in Thoroughbred racing, it is a common but harmful strategy for a horse to be ‘rated’ (held-back) during the early part of a race. Bit-free horses are trained to slow down without causing them pain and suffocation.

24. The physiology of respiration in the running horse requires a closed mouth, sealed lips, an outstretched head and neck, and a vacuum in the oral cavity (Cook 2020) (Figure 4).

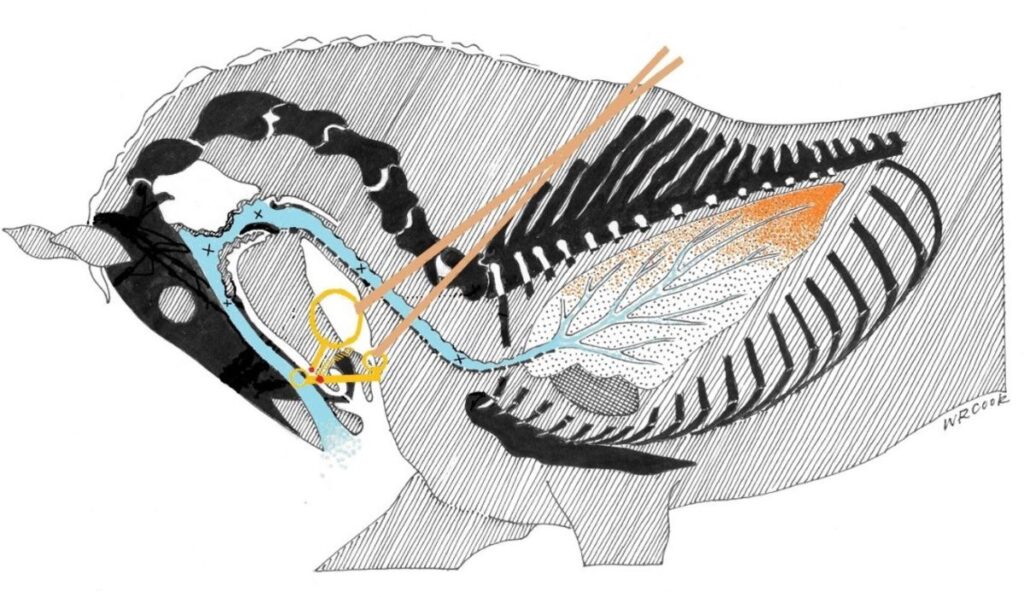

25. Mouth-metal usage obstructs a horse’s airway (Figure 5). Additional diagrams illustrate form and function (Cook 2024a).

Figure 5. Overbending in bit-ridden dressage horses results in intense mouth pain and creates a ‘U’ bend in the airway that obstructs airflow at the five points marked with a cross (x). Racehorses are often burdened with two bits, and sometimes with a tongue-tie. Though poll flexion in a racehorse is less extreme than in dressage, mouth pain is still intense, and airway obstruction can be severe due to elevation of the soft palate and strangling. The ultimate effect of the bit is to cause the rapid onset of lung edema (hence ‘bleeding’), physical exhaustion, poor performance, severe chest pain, a sense of drowning, existential fear, stumbling, falls, catastrophic accidents, and sudden death. Rather than complying with a painful signal, a horse’s natural response is to resent, resist, and refuse to respond. A rider needs to communicate more politely (i.e., painlessly), but this is not possible using a bit. Illustration by Dr Cook.

When breathing fails: The physiology of suffocation

26. Exercise associated sudden death (EASD) is defined as “a fatal collapse occurring during or immediately after racing or training, in a previously healthy individual, in the absence of a catastrophic orthopedic injury.” The phrase “previously healthy” raises an issue. The evidence indicates that a bit-ridden horse is a horse ‘at risk’ and ‘unfit to compete.’ A bit-ridden horse, in pain and asphyxiating at fast exercise, cannot be considered either healthy, safe to ride, or fit to compete.

27. To repeat, mandatory mouth-metal usage and the infliction of pain is incompatible with horse welfare, Learning Theory, and the spirit of a sport.

28. Figure 5 illustrates numerous points in the respiratory tract at which bit-induced airway obstruction occurs (additional diagrams at Cook 2024a). A law of physics governing airflow in tubes (Poiseuille’s law) explains why bit-ridden racehorses bleed from the lungs, become exhausted, stumble, fall, break bones, dislocate joints and die sudden deaths. Poiseuille’s law states that resistance to airflow increases with distance from the site of the obstruction. This explains why, with an obstruction at the level of the throat, severe bleeding (negative pressure pulmonary edema) first occurs in the tail end of both lungs, as illustrated in Figure 5, and quickly spreads forward – consolidating both lungs.

29. Visible signs of airway obstruction during exercise include an open mouth, lack of head/neck extension, overbending, and blood at the nostrils during or immediately after exercise. Endoscopic signs (at rest, or during exercise with overground endoscopy) include dislocation of the throat airway (dorsal displacement of the soft palate), epiglottal entrapment, laryngeal paralysis and partial paralysis. In human medicine, the symptons of lung edema caused by airway obstruction include severe chest pain, a sense of drowning, and intense fear. It is reasonable to infer that bit-induced asphyxia in the horse causes similar effects. Physical exhaustion could be a cause of stumbling, falls, catastrophic accidents, and sudden death from bit-induced asphyxia or from activation of a trigemino-cardiac reflex, i.e., a ‘heart attack’. (Chowdhury and Schaller 2015, Cook 2022b).

30. Exercise-induced hypoxemia (shortage of oxygen) in the racehorse is a recognized condition (Dixon 1982). The extraordinary length of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve could render this nerve especially vulnerable to damage from hypoxia, explaining why left-sided recurrent laryngeal neuropathy occurs with palpable atrophy of the left dilator muscle of the larynx in 91% of racehorses (Cook 1988).

Looking ahead, to the time when bit-free racing becomes the norm, and mouth-irons are disallowed, it may finally be realized that ‘roaring’ and other wind problems no longer occur, i.e., that bit-induced hypoxemia from elevation of the soft palate was the cause of recurrent laryngeal neuropathy.

Bit-induced poll flexion and elevation of the soft palate initiates suffocation at fast exercise by obstructing the throat airway (the first two crosses in Figure 5). Further obstruction from left-sided neuropathy may occur in the larynx (the third cross in Figure 5). Together, these two causes of upper airway obstruction result in increasingly severe dynamic collapse of the lower airway along the course of the windpipe in the neck (the fourth and fifth crosses in Figure 5), with the most severe obstruction at the level of the first rib and entrance to the chest. Repeated episodes of obstruction can lead to permanent deformity of the windpipe at this level (‘scabbard’ trachea). If an imaging technique could be developed for recognizing such a deformity, it would provide a means for identifying a racehorse at high risk of sudden death.

Nerves, reflexes and sudden death

31. The Trigeminal nerve is the sensory nerve to the whole of the head (Figure 1). As the name suggests, the nerve has three major branches; to the eye, upper jaw, and lower jaw. In the brain, the central fibers of all three branches are intimately entwined with another cranial nerve (the Vagus nerve) that regulates the heart. As a mouth-iron stimulates all three branches simultaneously, on both sides of the head, this explains why a bit-ridden racehorse might die of a heart attack from either activation of a trigemino-cardiac reflex or from vagal inhibition of the heart.

32. The cornea of the horse’s eye is another region of high sensitivity (Figure 6). On a wet track, the shod hooves of the horse in front scoop-up dirt and debris at every stride and kick it in the face of the following horse and jockey. An oculo-cardiac reflex is a recognized cause of cardiac arrest during eye surgery in man.

Figure 6. A jockey after a muddy horse race. The horse had no goggles. Image Dreamstime.com.

33. Because a bit repeatedly and simultaneously stimulates all three branches of the Trigeminal nerve, on both sides of the mouth, the bit is a common cause of headshaking (Cook and Kibler 2018). This bit-induced conflict behavior was all too obvious in the carriage horses at the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle (Fox 2018a b). As opined by veterinarian Michael Fox, “Obvious oral discomfort at a Royal Wedding. Time for the royal horse brigade to get with the times and put animal welfare and respect before blind tradition.”

34. The mouth-iron method is a form of invasive surgery. The etymology of the word ‘surgery’ means “a working with the hands.” It is a daily, invasive and aversive intervention without anesthesia, involving manual work from a distance while on the move. The method is based on the concept of ‘pressure and release’. However, though pressure is certain, release is not, this being dependent on the rider having an independent seat, a rare skill. When riders instinctively and understandably throw their body weight on both reins to retain their balance, no release occurs, quite the opposite. Similarly, while a dressage horse is kept ‘on the bit’ with rein tension for constant contact, there will be no release. A jockey, standing in the stirrups at a full gallop, will be balancing by applying pressure on both sides of a racehorse’s mouth.

The “pressure and release” concept has provided a comforting explanation for how the mouth-iron method conveys a rider’s instructions to a horse. There is, however, another explanation that needs consideration. The Cambridge Dictionary definition of slavery is, “The condition of being legally owned by someone and forced to work for or obey them. Shackles are the most potent symbols of slavery.” Another name for a bit is ‘a mouth shackle’.

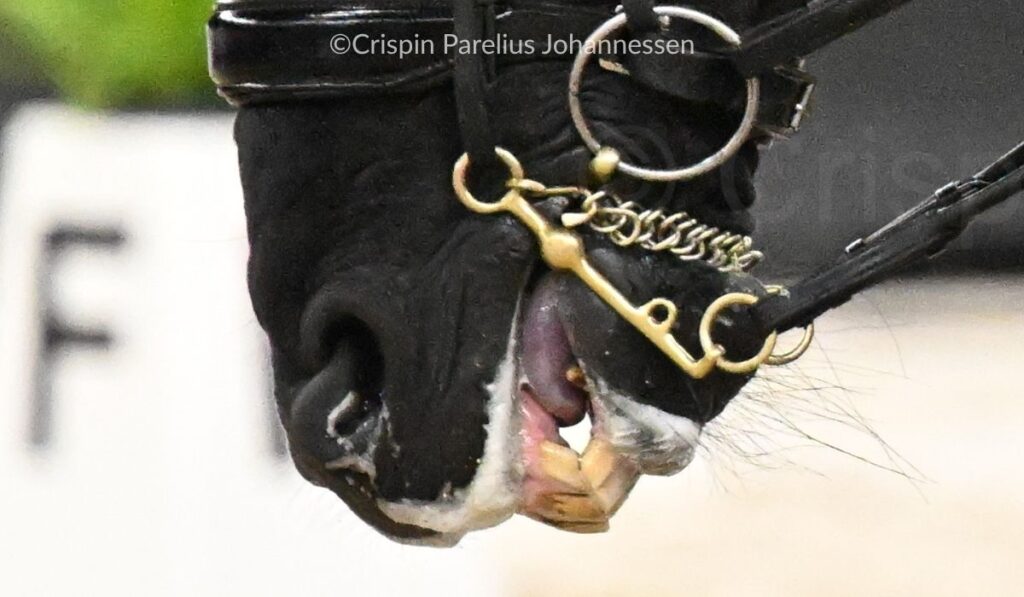

35. An important contribution to the science of horse sport has been made by Crispin Johannessen with his use of high-definition, evidentiary photography (Wilkins et al 2025). His images significantly enhance our recognition of a shackle’s harmful effects. In a 50-minute video, Johannessen and his colleagues comment on a library of photographic evidence that he compiled at two international dressage competitions this year. Once seen, this video cannot be forgotten. Gaping mouths, cyanotic (painful and swollen) tongues, and ‘wild’ eyes with sclera exposed tell the unhappy story.

Unless changes are made and shackle-free becomes an option, horse sport is at risk of losing its social license to operate.

Figure 7. A dressage horse in a double bridle. The snaffle and curb reins are taut. The nasal plane is close to the vertical, and the jowl angle illustrates airway obstruction. The lips are unsealed, so the airway will be further obstructed by soft palate elevation at each intake of air. Bit pressure will cause pain, particularly from the curb applying point pressure on the knife edge of periosteum at the bars of the mouth. Bit pressure has slowed the circulation of oxygenated blood to the tongue, hence its cyanotic color. Edema of the supraorbital fossa is apparent in Figures 8,15-17). Photo ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

Figure 8. A dressage horse in a double bridle at an international horse show, exhibiting clinical signs similar to Figure 7. The eyelids are swollen and there is swelling of the hollow above the eye. The tongue is cyanotic and swollen. ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

LEFT: Figure 10. A Dexter Ring bit. The lips are unsealed. The apex of the tongue is not as pink as it should be and is retracted, exhibiting its spatula-like conformation. RIGHT: Figure 9. The Dexter Ring Bit, a snaffle and ring bit. A type of ‘double bridle’ frequently used on racehorses. The intended purpose of the ring bit is to add to the severity of the snaffle, to keep the snaffle ‘centered’ in the mouth, and to prevent horses from getting their tongue over the bit. Image Dreamstime.com.

LEFT: Figure 12. ‘Rich Strike’ pre-race. Winner of the Kentucky Derby (2022), harnessed with a Dexter Ring Bit. The spatula-like conformation of a normal tongue’s apex is apparent. RIGHT: Figure 11. The Chiffney bit: a predecessor of the Ring Bit, sold as an anti-rearing bit and used for leading a horse from the ground. Whether it served its intended purpose is questionable. Any bit is a possible cause of rearing. Images supplied by Dr R. Cook.

Figure 13. Cyanosis of a swollen tongue. Compare its color with the healthy color of the gums. Note the vice-like action of the curb bit and chin chain on the jawbone. Photo ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

Figure 14. Showing the normal hollow above the eye of a healthy horse (anatomical name: the supraorbital fossa). Image Dreamstime.com.

Figure 15. An unhappy dressage horse exhibiting pain from a double bridle; an open mouth; a ‘wild’ and bloodshot eye; and swelling of what should be a concavity above the eye and below the browband (i.e., loss of the supraorbital fossa). Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

Figure 16. A close-up showing the blood-shot sclera of the eye and the swelling above the eye. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

Figure 17. A close-up of another horse with a ‘wild’ eye and the swelling above the eye, marked by a red spot at its front end. To explain the loss of the supraorbital fossa, it would be helpful to know if it occurs on both sides of the head. If it does, perhaps a combination of poll flexion, retraction of the tongue, and consequent swelling of the root of the tongue, is interfering with venous drainage from the head (see a clue in the caption to Fig. 17. Cook 2024a. The tongue as a muscular hydrostat). Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

Figure 18. Double bridle hyperflexion in a dressage horse at an international competition. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

The need for post-mortem data

36. Mandatory autopsy examinations of horses that have died on the racetrack will not disclose confirmatory evidence of the bit’s harm until autopsy protocols are updated, and their reporting standardized (Cook 2022b). Currently, autopsy reports are not required to list what bits were used; whether there was bit-induced damage to the bars of the mouth or the molar teeth; tracheal deformity; or laryngeal muscle atrophy from recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (a possible sequel to bit-induced hypoxemia of the recurrent laryngeal nerve).

Progress toward change

37. For the last 12 years or more, the Royal Dutch Equestrian Federation have allowed bit-free virtual dressage.

38. In 2024, thanks to the recommendation by Dr. Andrew McLean, the Australian Pony Club allowed its members, on application, to compete bit-free. Other Pony Clubs around the world are following suit.

39. The Danish Equestrian Federation is in the process of reviewing its rules and regulations

40. Dr. Niels Fuglsang has called on the Parliament of the European Union to protect sports horses by law; to ban ‘unfriendly’ equipment such as double bridles and other types of curb bit.

41. In 2024, an article was published in Poland with the subtitle, “When does sports autonomy become an excuse for animal abuse?” (Lubelska-Sazanow 2024) The article “aims to answer the questions of whether equestrian sports constitute a general exemption to their being considered animal abuse and on what grounds this exemption might be changed in the future.”

What remains to be studied

42. Important aspects of a horse’s ridden behavior await study. For example, what is the effect of a mouth-iron on a horse’s length of stride and speed? With the availability of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology, these are questions that could be answered. My expectation is that bit-free riding will be shown to increase both parameters, with the intensely interesting effect of increasing a racehorse’s speed.

43. In the study “Behavioural assessment of pain in 66 horses, with and without a bit,” (Cook and Kibler 2018), it was documented, for the first time, the significant degree by which 69 bit-induced pain behaviours were reduced by riding bit-free for a mean period of 30 days (see Table 1, Cook and Kibler 2018). The mean reduction was 87% (range 43–100%). Many of the bit-induced pain indices jeopardize the safety of horses and riders.

44. Long-term experience with the bit-free method has shown that improvement in behavior after a month, continues in succeeding months. Repeating assessments at 3, 6, and 12 months, document such improvements. The owner of one horse which, when bit-ridden, was dangerous to ride, reported that after the first month of substantial improvement, the horse continued to show further improvement for the next four years, at which stage the horse was completely rehabilitated.

45. Communication occurs from rider-to-horse and from horse-to-rider. Just as a rider’s use of a mouth-iron affects a horse’s behavior, it might be expected that the characteristically nervous and spooky behavior of a bit-ridden horse would affect a rider’s feelings about riding. In the second part of the questionnaire study (Cook and Kibler 2018), the effect of bit-induced pain in the horse on the rider’s feelings was studied for the first time (Cook and Kibler 2022). An additional ten questions were answered by 45 of the 66 riders who reported how their feelings about riding changed after they had ridden bit-free for about a month. When using a bit, 45 riders reported having 200 negative feelings about riding. When bit-free, they reported 18, a reduction of 91%. The rider’s feelings were negatively influenced by their horse’s aversion to a mouth iron.

46. As a ‘footnote’ (pun intended), another factor relevant to the question of heart attacks in racehorses relates to the health of the horse’s hoof. With the horse’s further domestication in the Middle Ages, two additional practices became customary: shoeing and stabling. These medieval handicaps negatively impact hoof health and horse welfare (Strasser and Kells 1998; Cook 2002b and see the website https://www.thehorseshoof.com/). The normal function of the hoof is to expand and contract at each step. This ensures a healthy blood supply to the hoof and retains its inherent flexibility. While galloping, each hoof acts as a supplementary vascular pump, assisting the action of the heart in maintaining blood flow throughout the body. The nailing of a metal clamp on each hoof interferes with the effectiveness of this function and places an additional burden on a heart that is already under stress. Bit-induced Negative Pressure Pulmonary Edema (‘bleeding) will massively increase resistance to blood flow through the lungs.

CONCLUSIONS

The Duke of Newcastle’s clear recommendation for bit-free horsemanship in the 17th century is notable as an early criticism of the bit. A bit-ridden horse is a horse at risk of injury and sudden death. Unless the bit problem is addressed, horseracing will lose its social license to operate. Now is the time to unshackle the horse. To summarize by borrowing Shakespeare’s phrase from Sonnet 129 about lust in man, it can be said that the horse’s bit is “murd’rous, bloody, full of blame, savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust.”

RECOMMENDATIONS

Bit-free trials to be conducted for all disciplines of horse sport. If the results are as supportive of pain-free sport as the evidence indicates they will be, mandatory bit rules can be taken off the books.

Horseracing Administrations are faced with a problem that lends itself to a convincing solution, accompanied by clear benefits. There will be no need to banish the bit. As unshackled horses begin to win races and break track records, the bit will hastily and voluntarily become a thing of the past, to be seen again only in museum collections of bygones.

Disclaimer: To make an unfamiliar design of bridle available, I marketed a bit-free bridle from 2000-2016*. Since 2016 I have had no conflict of interest to declare. Current address: PHS Saddlery, www.phssaddlery.com 5220, Barrett Rd., Colorado Springs, 80926.

REFERENCES and further reading:

- Beausoleil, N.J. and Mellor, D.J. (2015): “Introducing breathlessness as an animal welfare issue.” New Zealand Veterinary Journal 63, 44-51

- Bonner, J. (1998): “Changing Tack; horses may prefer bridles with a bit missing.” New Scientist, 4 July.

- British Horse Authority. (2022): “Welfare Strategy: A Life Well Lived.” https://www.britishhorseracing.com/press_releases/a

- Chowdhury, T and Schaller, B.J. (2015): “Trigeminocardiac Reflex” Academic Press, Elsevier Inc.,

- Cook, W.R. (1988): “Diagnosis and grading of the larynx for recurrent laryngeal neuropathy in the horse.” [by digital palpation of the larynx for evidence of muscle atrophy] Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, Volume 8, Issue 6, November–December 1988, Pages 432-455

- Cook, W.R. (1989): “Specifications for Speed in the Racehorse: the airflow factors” The Russell Meerdink Company, Menasha, WI, USA.

- Cook, W. R. (1993): “Exercise-induced Pulmonary Hemorrhage in the Horse is Caused by Upper Airway Obstruction.” Irish Veterinary Journal, 46: 160-161

- Cook, W.R. (1998a): “Use of the bit.” Veterinary Record, 142,16

- Cook, W.R. (1998b): “Use of the bit.” Veterinary Record, 142, 676

- Cook, W.R. (1999a): “Pathophysiology of Bit Control in the Horse. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 19(3):196-204 DOI: 10.1016/S0737-0806(99)80067-7

- Cook, W.R. (1999b): “The Ear, the Nose, and the Lie in the Throat.” Guardians of the Horse, Past, Present, and Future. British Equine Veterinary Association and Romney Publications, p175-182

- Cook, W.R. (1999c): “Asphyxia as the cause of bleeding and the bit as the cause of soft palate displacement.” Thoroughbred Times, Guest Commentary. November 27, 18-19.

- Cook, W.R. (2000): “A solution to respiratory and other problems caused by the bit.” Pferdeheilkunde, 16, 333-351

- Cook, W.R. (2001a): “The Penalties of the Bit and the Benefits of Bitlessness.” Pferdegesunde

- Cook, W.R. (2001b): “On Talking Horses: Barefoot and Bit-free.” Natural Horse Magazine, 3, 19

- Cook, W.R. (2001c): “Who Needs Bits?” Natural Horse Magazine 3, 44-47

- Cook, W.R. (2001d) “Alternative Drooling Research”. Dressage Today. November. p15

- Cook, W.R. (2002a): “Bit-induced Asphyxia in the Horse: Elevation and Dorsal Displacement of the Soft Palate at Exercise.” Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 22, 7-14 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0737-0806(02)70207-4

- Cook, W.R. (2002c): “On ‘Mouth Irons’, ‘Hoof Cramps’, and the Dawn of the Metal-Free Horse.” Natural Horse, August 2002, vol 4, issue 4, pp 37-40

- Cook, W.R. (2002d): “No bit is best.” Thoroughbred Times, October 19, p18

- Cook, W.R. (2003a)): “Bit-induced Pain; a cause of fear, flight, fight and facial neuralgia in the horse.” Pferdeheilkunde, 19, 1-8

- Cook, W.R. (2003b): “Fear of the Bit: A Welfare Problem for Horse and Rider”. Parts I-III. Available with others at www.bitlessbridle.com/ Part I “Why Horses Hate the Bit.”; Part II “Bit-induced Diseases and other Indictments.” ; Part III “Behavioral Profiling Questionnaire.”

- Cook, W.R. (2011): “Damage by the bit to the equine interdental space and second lower premolar.” Equine Veterinary Education, 23, 7, (355-360)

- Cook, W.R. (2012): “Why do veterinarians not apply available knowledge?” Chapter VII. “Free your horse; free yourself” by Maksida Vogt, Cadmos, Germany

- Cook, W.R. (2013): “An endoscopic test for bit-induced nasopharyngeal asphyxia as a cause of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage in the horse.” Equine Veterinary Journal. 2014;46:256–257. doi: 10.1111/evj.12205. – DOI – PubMed

- Cook, W.R. (2014): “A hypothetical, etiological relationship between the horse’s bit, nasopharyngeal asphyxia and negative pressure pulmonary oedema,” Equine Veterinary Education, 26, 7, (381-389), (2014).

- Cook, W.R. (2016a): “Feel it, log it, fixit: Prevention of accidents under saddle.” The Horse’s Hoof, Fall issue, pp 34-45

- Cook, W.R. (2016b): “Bit‐induced asphyxia in the racehorse as a cause of sudden death.” Equine Veterinary Education 28, 405-409 https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.12455

- Cook, W.R. (2018): “Unintended consequences in preparing ‘the big horse’ for the ‘big day’. HorseTalk, New Zealand

https://www.horsetalk.co.nz/2018/12/09/unintended-consequences-preparing-big-horse/ - Cook, W.R. (2019a): “Horsemanship’s ‘elephant-in-the-room’ – The bit as a cause of unsolved problems affecting both horse and rider.” Weltexpress: https://en.weltexpress.info/2019/02/15/horsemanships-elephant-in-the-room-the-bit-as-a-cause-of-unsolved-problems-affecting-both-horse-and-rider/ [Accessed 7/9/2025]

- Cook, W.R. (2019b). “Man bites horse.” Horses and People 061819

- Cook, W. R. (2019c): “Clearing the Air on the Bit-free Debate.” Horses and People Magazine, November-December issue.

- Cook, W.R. (2022a): “Does use of a bit endanger the health and safety of horse and rider?” https://worldbitlessassociation.org/resources/does-use-of-a-bit-endanger-the-health-and-safety-of-horse-and-rider-professor-robert-cook-july-2022/

- Cook, W.R. (2022b): “Sudden death in the racehorse.” https://worldbitlessassociation.org/resources/sudden-death-in-the-racehorse/

- Cook, W.R. (2023a): “Why not bit-free? Expert says it is time to draw the equestrian Iron Age to a close.” Horse and People. [the article documents the chronology of equine welfare development.]

- Cook, W.R. (2023b): “Sustaining the social license for equestrian sport.” Horses and People Magazine.

- Cook, W.R. (2023c): “Data and visual evidence for the bit-free debate.” Data and Visual evidence for the Bit-free debate – World Bitless Association

- Cook (2024a): “A bit-free, pain-free future for the free-breathing horse.” Horses and People Magazine. https://horsesandpeople.com.au/a-bit-free-pain-free-future-for-the-free-breathing-horse/

- Cook (2024b): “The evidence for allowing a bit-free option in equestrian sport.” Horses and People Magazine

The Evidence for Allowing a Bit-Free Option in Equestrian Sport (horsesandpeople.com.au) - Cook (2024c): “Horse Sports’ Option: Ban or be Banned.” Horses and People Magazine. https://horsesandpeople.com.au/horse-sports-options-to-ban-or-be-banned/

- Cook, W.R. (2024d): “Critique of the film ‘Horses and the Science of Harmony’.” Horses and People Magazine.

- Cook, W.R, Williams R.M, Kirker-Head, C.A. and Verbridge, D.J (1988): “Upper Airway obstruction (partial asphyxia) as the possible cause of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage in the horse: a hypothesis.” Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 8: 11-26

- Cook, W.R. and Strasser, H (2003): “Metal in the Mouth: The Abusive Effects of Bitted Bridles.” Sabine Kells, Qualicum Beach, BC, Canada.

- Cook, W.R. and Mills, D.S. (2009). “Preliminary study of jointed snaffle bridle vs. crossunder bitless bridle: A quantified comparison of behaviour in four horses.” Equine Veterinary Journal, 41 (8) 827-830 doi: 10.2746/042516409X47215

- Cook W.R. and Kibler, M. (2018): “Behavioural assessment of pain in 66 horses, with and without a bit.” Equine Veterinary Education. https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.12916 [Table 1 lists the behaviors in order of frequency and documents the percentage improvement in each behavior following removal of the bit]

- Cook, W.R. and Kibler, M (2022): “The effect of bit-induced pain in the horse on the feelings of the rider.” https://worldbitlessassociation.org/resources/the-effect-of-bit-induced-pain-in-the-horse-on-the-feelings-of-riders-about-riding-2022/

- Dixon. P.M. (1982): “Arterial blood gas values in horses with laryngeal paralysis.” PMID: 6809457 DOI: 10.1111/j.2042-3306. 1982.tb 02407.

- Douglas, J, Owers, R, and Campbell, M. L.H. (2022): “Social License to Operate: What Can Equestrian Sports Learn from Other Industries?” Animals 2022, 12(15), 1987; https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151987 2

- Equine Veterinary Journal Collection from IFHRA Summit “To improve racehorse safety,” (2024). https://www.beva.org.uk/News/Latest-News/Details/EVJ-highlights-ongoing-work-to-improve-racehorse-safety?fbclid=IwY2xjawK2OmhleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHvCgmQ66LHcZoGozmjApNs6Ay2GewKOAckLb3aN–CPB_8_YNUsUmfE1EE80_aem_TfrtL34oYlAXuuPJzjWk5g&sfnsn=scwspmo

- Fox, M.W. (2018a). “Horses at the Royal Wedding.” Veterinary Record, vol182, Issue 21, p608-608

- Fox, M.W. (2018b) “The Royal Wedding and Horse Welfare.” Animal Doctor, June 10th, 2018

- Froment, A (2024): “The Horses Who Made Me: A Journey to a Horsemanship Philosophy.” Trafalgar Square, North Pomfret, Vermont, USA

- Garnham, J. (Mellor D.J.) (2024a). “Thoroughbred Horse Welfare Challenges: From Rape to Relegation.” Horses and People, July 2024: https://horsesandpeople.com.au/thoroughbred-welfare-challenges-from-rape-to-relegation/

- Garnham, J. (Mellor D.J.) (2024b). “Improving Sports’ Horse Welfare: A Way Forward.” Horses and People, September 2024: https://horsesandpeople.com.au/improving-sports-horse-welfare-a-way-forward/

- Garnham, J. (Mellor D.J). (2024c). “Seven Pillars of Deception to Delay Action on Horse Welfare,” Horses and People, October 2024: https://horsesandpeople.com.au/seven-pillars-of-deception-delaying-action-on-horse-welfare/:

- Garnham, J. (Mellor, D.J). (2025). “The Sieve Telling the Needle It has a Hole in Its Back: Illustrating Two Approaches to Equine Sports Welfare Research. Horses and People; August 2025: https://horsesandpeople.com.au/the-sieve-and-the-needle-two-approaches-to-equine-sports-welfare-research/

- Hanson, F and Cook, W.R. (2017): “The Bedouin Bridle Rediscovered; A welfare, safety, and performance enhancer.” The Bedouin Bridle – weltexpress.info

- Harvey, A. (2023): “A Bit of a Problem in Equine Welfare: What is the Role of Veterinarians?” Center for Veterinary Education, Control and Therapy Series, Number 6001. Issue 313, pp23-26. 8.

- IFHRA (2024): “International Federation of Horseracing Authorities’ Horse Integrity Handbook.”

- Hopkins E.R, Whitrod, S, Marlin, D, and Blake, R (2025): “Tight nosebands apply high pressure on the horse’s face and alter stride kinematics.” Journal of Veterinary Science https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2025.105654

- Jockey Club (2019): White Paper RACING. Vision 2025. To Prosper, Horse Racing Needs Comprehensive Reform.” http://www.jockeyclub.com/pdfs/vision_2025_updated.pdf

- Keen, J, Whitton, (2024): “IFHA Global Summit on Equine Safety & Technology: What veterinary scientists want from racing.”:

https://beva.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/evj.14432 - Lyle, C.H, Blissit, K.J. Kennedy, R.N, McGorum, B.C, Newton, J.R, Parkin, T.D.H, Stirk, A, Boden, L.A. (2011). “Risk factors for race-associated sudden death in Thoroughbred racehorses in the UK.” Equine Veterinary Journal, vol 44, issue 4, July2012, pp 377-500.First published: 01 December 2011 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00496.

- Lubelska-Sazanow, M (2024): “Ethics in sports industry: When does sports autonomy become an excuse for animal abuse?” International Journal of Law in Context, 1–17 doi:10.1017/S1744552324000193

- Mellor, D.J. (2019a): “Equine welfare during exercise 1. Do we have a bit of a problem?” Scribd Everand.

https://www.slideshare.net/SAHorse/equine-welfare-during-exercise-do-we-have-a-bit-of-a-problem - Mellor, D.J. (2019b): “Equine welfare during exercise 2. Do we have a bit of a problem?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rY4yEC71hco

- Mellor, D.J. (2020): “Mouth Pain in Horses: Physiological Foundations, Behavioural Indices, Welfare Implications, and a Suggested Solution.”: Animals https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/10/4/572

- Mellor, D.J. (2024): “Kiwi’s statue reveals striking welfare message.” horsesandpeople.com.au/kiwi-sculpture-welfare-message/ Horses and People

- Mellor, D.J. (2025): “Machinations About Mouth Pain in Dressage Horses”. Horses and People. 17 March 2025. Available online: https://horsesandpeople.com.au/machinations-about-mouth-pain-in-dressage-horses/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Mellor, D.J. and Beausoleil, N.J. (2017a). “Equine welfare during exercise: An evaluation of breathing, breathlessness and bridles.” Animals 7(6), 41;

doi:10.3390/ani7060041 or http://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/7/6/41 - Mellor, D.J. and Beausoleil, N (2017b): “More pressure on the bit. Researchers talk of a significant welfare issue.” Horse Talk. https://www.horsetalk.co.nz/2017/09/01/pressure-bit-animal-welfare-issue/

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. “The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human–Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare.” Animals 2020, 10, 1870.

- Mellor, D.J. and Uldahl, D.M (2025): “Translating Ethical Principles into Law, Regulations and Workable Animal Welfare Practices.” Animals 2025, 15(6), 821; https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15060821

- Shakespeare, W (1593): “Venus and Adonis.”

- Strasser, H. and Kells, S (1998): “A lifetime of Soundness: The Keys to Optimal Horse Health, Lameness Rehabilitation, and the High-Performance Barefoot Horse.” Third edition (revised). Sabine Kells, Qualicum Beach, BC V9K 1S7, Canada,1998

- Stier, J. (2024): “IFHA Global Summit on Equine Safety & Technology: Racing’s concerns and what it expects from science.” |https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.14410

- Taylor, J (2022): “I Can’t Watch Anymore: The case for dropping equestrian from the Olympic Games. An open letter to the IOC.” Epona Media Copenhagen www.epona.tv

- Uldahl, M and Clayton, H.M (2018): “Lesions associated with the use of Bits, Nosebands, Spurs and Whips in Danish competition horses.” Equine Veterinary Journal, 51,154-162

- Uldahl, M. and Mellor, D.J. (2025). “Regulatory Integrity and Welfare in Horse Sport: A Constructively Critical Perspective.” Animals 15, 1934. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131934

- Wilkins, C.; Henshall, C. McGreevy, P, Mellor, D.J. Tuomola, K; Johannessen, C.P; Lykins, A. (2025): “Welfare in Dressage: Visual and Scientific Evidence. A 50-minute briefing entitled ‘Equipment-induced Pressures Affecting Sport Horses’. Evidence and welfare impacts.’ delivered to the FEI Veterinary Committee on 9 April 2025.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W6OgVEC4i28

- Wilkins, C (2025): “Foam, Fear, and False Signals. Why the FEI’s Ban on Artificial Saliva Matters.” https://horsesandpeople.com.au/foam-fear-and-false-signals-why-the-feis-new-ban-on-artificial-saliva-matters/