Next month, the FEI is expected to approve a rule change that would downgrade visible bleeding from the horse’s mouth or nose from an elimination offence to an administrative warning – effectively lowering the stakes for riders, and placing the sport’s “welfare is paramount” rhetoric at odds with its fragile social licence.

Instead of using this moment to strengthen the so-called “blood rule” – recognising the inherent risk of bit-induced trauma, and introducing proper veterinary oral-examination protocols for all competing horses – the FEI is proposing a move in the opposite direction.

The Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) was founded to safeguard equestrian sport’s place on the Olympic stage. In recent decades, that mission has increasingly depended on maintaining public trust and acceptance — the sport’s social licence to operate — by assuring that horse welfare is paramount and never subordinate to competitive interests. Yet despite decades of policy updates and welfare rhetoric, welfare outcomes in elite competition are not improving.

The latest proposed change to the so-called blood rule suggests the sport may now be jumping backwards.

From Elimination to Administration

Until now, Article 241 of the FEI Jumping Rules has been clear: if a horse bleeds from the mouth or flanks, the combination is eliminated. In minor cases — such as “where a horse appears to have bitten their tongue or lip” — officials were allowed to authorise the rinsing and wiping of the mouth once and allow the athlete to continue, but any further evidence of blood resulted in elimination.

Under the new proposal, to be voted on at the FEI General Assembly in November, bleeding will no longer fall under eliminations at all. Instead, a new Article 259 will classify blood on a horse as a Recorded Warning.

-

If blood is judged to have been caused by the athlete or by tack or equipment, the rider will receive a warning, not elimination.

-

Only after two warnings in 12 months will a rider face a fine and one-month suspension.

-

In cases where the horse is said to have “bitten its tongue or lip” or to be “bleeding from the nose,” officials may simply wipe away the blood and allow the horse to continue, provided the Veterinary Delegate agrees that the horse is “fit to compete” — and no warning will be recorded.

The term minor blood has been removed from the new rule — not, it seems, because the FEI now considers the term ethically troubling, but because it was difficult to enforce. The revision is no clearer; it places officials under pressure, is just as hard to apply and just as easy to defend when challenged, particularly since the FEI still has no official protocol for inspecting horses’ mouths for internal injuries.

Intent or Consequence?

In animal welfare terms, if a horse is bleeding from the mouth or nose during competition, the issue is tissue damage, not whether it was intentional or accidental. To suggest that blood in the mouth may be inconsequential while the horse is being ridden over a demanding track, in a bitted bridle that is being manipulated and pulled on by a rider in every turn and stride-length adjustment, is to misunderstand physiology, welfare and the risks of modern show jumping.

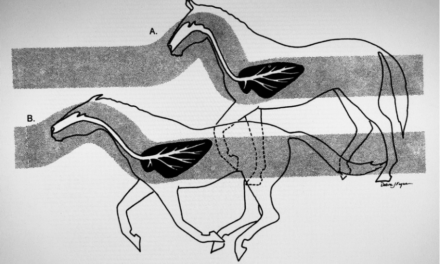

In today’s high-stakes show-jumping, efficient control is often achieved with mechanical force. Every stride adjustment, every turn command is transmitted through bits and reins to the horse’s head and mouth — it carries a high risk of oral injury. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

Over the past two decades, show jumping itself has evolved into a far more technically demanding and physically extreme sport. The tracks are now as high and wide as horse biomechanics allows, with lighter poles, flatter cups, and more complex distances between fences. Designers remove ground lines to make it harder for horses and riders to judge the take-off point. Even the smallest miscalculation risks a penalty. As the physical and technical demands have escalated, so too has the pressure on riders to maintain absolute control – and that pressure is expressed through the equipment.

It is no coincidence that the rise of hyper-technical courses has coincided with an explosion in combination bits and restrictive nosebands. All are designed to control horses who are expressly trained to be hyper-reactive. The French Parliament’s 2022 report on improving equestrian welfare for the Paris 2024 Olympics recommended a blanket ban on combination bits. It didn’t happen then and it is unlikely to happen now because riders have come to depend on mechanical-force systems of horse control.

The pursuit of technical precision leads to increasingly ‘efficient’ control strategies. Levered bits and tight nosebands magnify rein pressure, and tight nosebands limit the horse’s ability to protect their sensitive oral tissues from pressure. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

This climate has allowed shifts of ethical responsibility away from governance and onto individuals. Riders and officials are told it is their duty to “protect horses,” yet the governance system rewards exactly the opposite behaviour. Every rule change alters the incentive structure, and this one, by removing elimination for bleeding and continuing to allow injured horses to remain under ‘effective’ bridle control systems, lowers the severity of the penalties of pushing horses beyond welfare boundaries.

An Impossible Dilemma

Veterinarians and officials are then left to make the impossible judgement call: welfare or competition? The decision sounds straightforward in policy language but is nearly unworkable in practice, especially under the time pressures and the economic and political stakes of elite sport.

The FEI has removed most restrictions on the types of bits used in show jumping. It is mostly up to the Ground Jury, based on veterinary advice, to determine whether a specific piece of equipment may cause injury to the horse, which is interesting given that research shows any bit may cause injury (e.g., this study, this study, this study, this study, this study, this study, this study, and this study).

The regulatory approach leaves horses unprotected until bleeding occurs twice, failing to mitigate the known risks of bit-induced harm.

Conflicts of Interest and the Limits of Perspective

The International Jumping Riders Club (IJRC) and several national federations, including the Irish, proposed the administrative change. Their rationale appears to be that it is unfair for riders to be eliminated for unintentional injuries — a claim that reveals an enduring conflict of interest between competition and care.

This conflict was illustrated in a pilot study included in a PhD thesis, by Finnish veterinarian and welfare researcher Dr Kati Tuomola, who presented veterinarians and their assistants, trainers, and grooms with photographs of bit-related oral injuries. When asked whether they would allow the horse to start in an important race, vets and their assistants were, statistically, the most likely to say yes, and grooms the least.

It is a troubling finding. How does it happen that those expected to know the most about horses’ welfare were the ones most willing to overlook visible and painful lesions? We do not yet understand enough about how people make welfare-related decisions, and how professional distance, peer norms, and performance pressure interact to shift moral boundaries sufficiently to rationalise harm. This example shows it is not simply a matter of knowledge or education but of psychology and culture, and it urgently warrants investigation.

The blood rule change codifies that type of rationalisation. By treating visible bleeding as potentially inconsequential, and a procedural matter rather than a welfare risk, it embeds the same bias into regulation itself, incentivising the tendency to overlook the horse’s experience when performance is at stake.

When blood is visible, it signals tissue trauma that has already occurred. Allowing such horses to continue is the opposite of risk management. It means accepting a known injury while the same mechanical pressures continue to act on the damaged tissue through bits, nosebands, and the extremes of rein tension that are inevitable in the arena.

And yet, Tuomola’s wider research also demonstrated that even severe bit injuries most often do not bleed externally. Without systematic oral examinations by a trained dental veterinarian, how often horses are being made to perform with unrecognised pain and oral injuries?

Between the jumps lies the reality rarely shown. These moments — when control over stride length and line are enforced through the reins — reveal far more about the pressures of modern show-jumping than the elegant flight photos that dominate media coverage. All images ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen.

The accompanying photographs from this year’s show-jumping event at Falsterbo, Sweden, demonstrates this as reality: horses’ mouths contorted, lips compressed, tongues displaced, eyes wide with tension — as riders ride “effectively” and get a very difficult job done.

Yet the new rule implicitly asks us to accept a fiction — that the horse can’t feel it and that despite the presence of bits and other head gear, the bleeding could have happened “accidentally,” i.e., that the rider and equipment had nothing to do with it and, therefore, the horse is not at risk of further harm if they are required to continue.

This disconnect between evidence and accountability is at the core of the problem. When both the risk and visible consequences of bit and bridle pressures are dismissed as inconsequential, the welfare principle that competition must never override protection of the horse ceases to mean anything at all.

It also exposes a deeper failure of perspective: a sport that cannot see the impact of bits and bridles on the horse’s experience cannot meaningfully claim to protect it. Until the horse’s point of view is included in how welfare is judged, decisions will continue to be made from only one side of the reins, and public trust will continue to wane.

The Cost of Looking Away

The dilemma is not theoretical. It has already played out in full view of the world.

At the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, the Irish horse Kilkenny completed his round bleeding visibly from the nose because the team was in medal contention and no one felt empowered to intervene. The proposed rule does not address that scenario; it normalises it.

If this change is adopted some will say that “common sense has prevailed.” Riders may feel they have “won”, being spared from eliminations they perceive as unfair. But the sport itself will lose. Public tolerance for visible suffering in animals used for entertainment is shrinking rapidly, and the FEI’s credibility as a governing body depends on its ability to anticipate, not react to, that shift.

Each scandal erodes public trust. When horses bleed or struggle on the world stage, the question is no longer about whether they will die or suffer permanent damage or who’s to blame – it’s about whether equestrian sport can afford to leap backwards and be seen as a blood sport.

Losing the Plot and the Licence

The FEI’s problem is about both enforcement and direction. By reducing what was intended to be a welfare safeguard to an administrative warning, the organisation is signalling that competitive continuity matters more than animal integrity. That message runs directly counter to the Olympic Charter’s commitment to fair play, respect, and humane values.

The key question remains unanswered: who at the FEI is asking horses how they feel?

If the answer is “no one,” then the FEI is not managing its social licence, it is spending it.

What You Can Do – to Protect Horses and Horse Sports

The proposed change to the FEI Blood Rule is not yet approved. Stakeholders and members of the public still have the opportunity to express their views before the FEI General Assembly votes in November.

If you believe that equestrian sport should never become a blood sport, now is the time to speak up.

Write to the FEI (info@fei.org) and to your National Federation, urging them to oppose the reclassification of bleeding as a mere administrative warning – and to implement stricter controls and transparency around bit- and bridle-related injuries.

This is not just an issue for show-jumping. Every equestrian discipline depends on public trust, and when one sport normalises injury, all are tainted. The future of equestrian sport — and its fragile social licence — depends on drawing that line clearly, and keeping it there.