A medical doctor explains why tongue discolouration isn’t cosmetic—and what it reveals about equipment, anatomy, and welfare.

As a medical doctor, qualified horse trainer, human personal trainer, and bit and bridle fitting consultant, Dr James Cooling brings a rare and valuable perspective to the recent controversy in international horse sports: the emergence of “blue tongue” in elite sport horses—not because it’s new, but because, thanks to high-speed photography, we’re finally seeing it. In this article, he explains why even a fleeting glimpse of this phenomenon is far from trivial, and what it reveals about equipment, anatomy, and horse welfare. With social licence under growing pressure, his analysis couldn’t be more timely.

Drawing on physiology and anatomical insight, and decades of medical evidence, Dr Cooling explores how tongue discolouration occurs, why it signals compromised welfare, and how in combination with noseband pressures, a bit can act like a tourniquet inside the horse’s mouth. From the physiology of cyanosis to the ethics of judging practices, this is a deep and essential examination of a problem that must not become normalised.

Figure 1. The equine tongue performs many essential functions, including grasping, selecting, tasting, chewing, licking, discarding, and swallowing food. It is densely innervated and extremely sensitive to pressure, temperature, and pain. Left image by Linda Zupanc. Right image Dreamstime.com.

If it’s not pink, it’s not normal

Some commentators have expressed uncertainty about why “blue tongue” occurs in horses, or why we’re only noticing it now. Some suggest it can be a transient or incidental finding even in unridden horses and that further research is needed into this “new phenomenon.”

However, horses, like most mammals, naturally have a pink tongue.

Understanding the equine tongue

To understand why changes in tongue colour matter, and why they may signal a serious welfare concern, we need to look more closely at the tongue itself: its structure, function, and the unique vulnerabilities that make it especially sensitive.

Tongue structure and function:

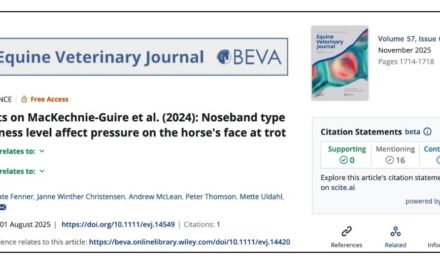

The tongue is a muscular hydrostat made entirely of muscle, with no bones or joints, it is capable of highly complex movement. Like an elephant’s trunk or an octopus’s tentacle, it can bend, twist, flatten, and arch while maintaining a constant volume. Volume constancy is important when considering how it may be affected by pressure from bits and bridles.

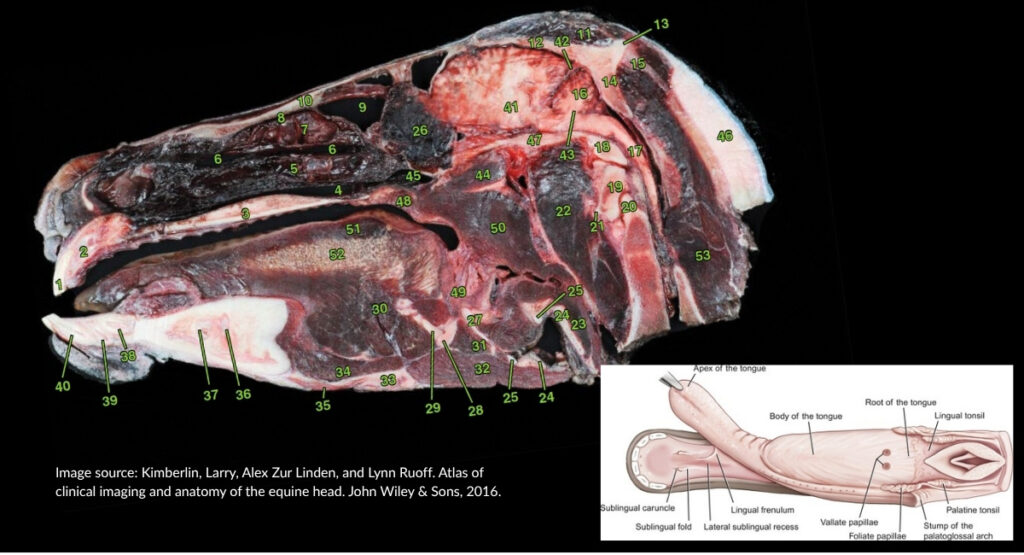

In a relaxed, resting horse with a closed mouth, the tongue fills the available space in the oral cavity. It sits between the lower jaw and the hard palate, occupying the full vertical and lateral volume. When the horse extends the tongue (for example, to lick or chew), it flattens and narrows, but its volume stays the same. Introducing additional objects, such as a bit (or two bits in the case of a double bridle), compresses the tongue against surrounding structures. This can restrict the tongue’s blood flow and cause pain or discomfort.

Figure 2. The tongue is a muscular hydrostat made entirely of muscle, with no bones or joints, it is capable of highly complex movement. Like an elephant’s trunk or an octopus’s tentacle, it can bend, twist, flatten, and arch while maintaining a constant volume. Image adapted from Kimberlin, Larry, Alex Zur Linden, and Lyn Ruoff. ‘Atlas of clinical imaging and anatomy of the equine head.’

Innervation and sensitivity:

The equine tongue performs many essential functions, including grasping, selecting, tasting, chewing, licking, discarding, and swallowing food. It is densely innervated and extremely sensitive to pressure, temperature, and pain. The front two-thirds are especially sensitive due to rich innervation by the trigeminal nerve. The surface is covered in papillae, small textured projections that increase tactile and chemical sensitivity.

Blood supply and circulation

The tongue is also highly vascular. In some mammals, the anterior third contains over 1,200 blood vessels per square centimetre, highlighting the importance of uninterrupted circulation. Blood is supplied via the common carotid artery, which branches into the external carotid and then the lingual artery. The lingual artery passes beneath the hyoglossus muscle before dividing into the deep lingual artery (supplying the tongue body) and the sublingual artery (supplying the underlying tissues).

Figure 3. In a relaxed, resting horse with a closed mouth, the tongue fills the available space in the oral cavity. It sits between the lower jaw and the hard palate, occupying the full vertical and lateral volume. When the horse extends the tongue (for example, to lick or chew), it flattens and narrows, but its volume stays the same.Composite image by Torbjorn Lundstrom adapted with permission by Horses and People.

When sensitivity becomes a control point

The tongue’s sensitivity and its connections to other parts of the body have traditionally been exploited to control the horse’s movements, speed and direction via bit pressure. If this is not applied with extreme tact and sensitivity, if contact is prioritised over self-carriage and the lightest rein tension, if the equipment is poorly designed or poorly fitted for the individual horse, it increases the risk of injury or tongue restriction. This can have immediate and serious impact on the horse’s physical and psychological welfare.

Figure 4: The tongue’s sensitivity and its connections to other parts of the body have always been exploited to control the horse’s movements, speed and direction via bit pressure. Images sourced online.

Recognising and interpreting tongue discolouration

Some have claimed that it’s “impossible to determine if a tongue is discoloured.” This is easily disproven by anyone with a basic understanding of equine anatomy and physiology.

Normal vs abnormal tongue colour

Simply put: if it’s not pink, it’s not normal. There is ample evidence to support this standard.

While a few mammalian species, such as giraffes and certain dog breeds, naturally have dark-pigmented tongues, this does not apply to horses. In horses, unless they have eaten something that explains a temporary but harmless discolouration (e.g., a few blackberries), a tongue that is not pink indicates a problem, one that warrants further and possibly urgent investigation to determine the underlying cause.

Medical causes unrelated to tack and equipment:

If tongue discolouration is observed in a horse that is not wearing tack or being ridden, it is likely to indicate an underlying medical issue. Possible causes include respiratory compromise, cardiovascular or circulatory dysfunction (e.g., low blood oxygen), or systemic conditions such as anaemia, any of which may require urgent veterinary attention.

Mechanical causes in ridden horses:

However, in a horse being ridden in a bit, bridle, or double bridle, particularly at elite or FEI level, these causes are far less likely. In such cases, tongue discolouration is more likely to be acute and related to the fit or use of the bit, bridle, or noseband. The risk may be further exacerbated in horses trained in a posture that promotes over-development of certain neck muscles, a hollow frame, and “leg movers” rather than “back movers”.

Figure 5. Note the outline of the tongue touching the palate in the composite X-ray image, and how even a simple snaffle significantly compresses the resting tongue. The volume constancy of the tongue as a muscular hydrostat is important when considering how the tongue may be affected by pressure from bits and bridles. Image composite by Torbjorn Lundstrom adapted with permission.

Case studies from practice

In my work as a bitting consultant, I have encountered ‘blue tongues’ several times with both double and snaffle bridles, in ridden and unridden horses.

I have documented various cases of poorly fitting double bridle bits causing a blue tongue to appear in the stable, before the horses were ridden or the rein contact was applied. The issue was simply that there wasn’t enough space in the oral cavity for two bits, resulting in significant tongue compression. In both cases, the horses became visibly withdrawn and shut down shortly after being tacked up.

Compression before the ride:

In one horse, the tongue colour returned to normal once the noseband was loosened in the stable to allow more than 2-fingers gap between the strap and the nasal bones, although a bit change was also required. In another, the bit mouthpieces were too thick and crossed over each other, exacerbating the compression. The rider had been advised to tighten the noseband to prevent the horse from opening the mouth, which only worsened the issue as well as preventing the horse from easing the pressure and pain. This case also required a complete change of bit and bridle before any ridden assessment could take place.

Tongue discolouration during work:

I have also observed tongue discolouration during ridden assessments, including in snaffle bridles. In these cases, it was associated with poor bit fit or excessive bit thickness, overly tight nosebands, poor head and neck posture, and rein contact issues.

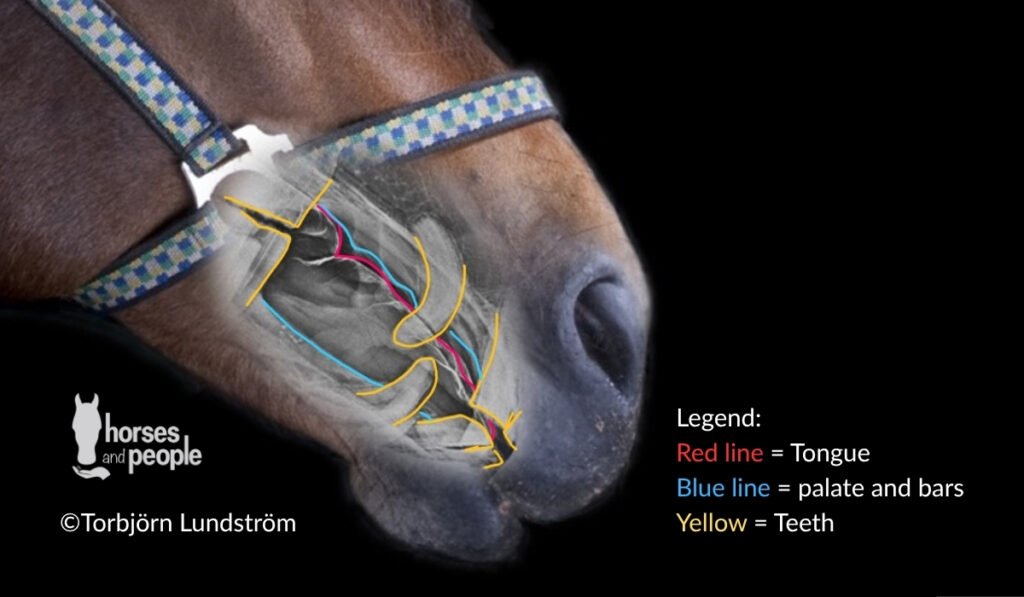

Behavioural signs and learned helplessness:

Of note, none of the horses I have observed with a discoloured tongue during a bit-fitting session showed obvious resistances to being bridled or ridden. This may indicate some degree of learned helplessness if they have experienced and failed to resolve bit-related pain in the past.

Because of their natural history, horses tend to move into pressure (positive thigmotaxis). This could be an instinctive response to detecting an attempt to restrain their movement and flight. This escape or avoidance response, driven by adrenaline, motivates forward movement at any cost, which is then often misinterpreted as ‘willingness’ and used by the rider to achieve more spectacular paces.

This dynamic becomes clearer when pressure is reduced, for example, by loosening the noseband or switching to a milder bit. Many horses immediately appear calmer and less reactive, shifting out of a flight state. In contrast, when nosebands are tight, the horse may feel unable to escape the pain caused by bit pressure. This sense of entrapment can intensify the flight response.

If the horse instead slides towards a ‘freeze’ state (stalling or shutting down), the rider may override this with stronger driving aids. These include leg, spur, or whip signals – pressures from which the horse receives intermittent relief, and which are removed when the horse goes forward. Soon, the horse may focus on the “go forward” aids and stop paying attention to the mouth pain. This can result in the horse appearing to become ‘dead’ or ‘hard’ mouthed. However, the attentional shift happens because they have learned that they can achieve a release from leg and whip pressures, but not the bit pressure, since nothing they try resolves that particular source of pain.

All these patterns present serious welfare issues.

Figure 6. The myth that horses will not perform when experiencing oral pain. The horses the author has observed with a discoloured tongue during bit-fitting consults showed no obvious resistances to being bridled or ridden. This may indicate some degree of learned helplessness if they have experienced and failed to resolve bit-related pain in the past. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen. Do not reproduce without permission.

Blue tongues are not a new phenomenon, nor are they confined to elite competition horses. They can occur in any bitted horse, at any level.

As equine professionals, it is essential to understand the potential harms caused by poorly fitted bits and bridles—and to apply enough professional curiosity to routinely check the horse’s mouth when there is any change in behaviour during tacking up, or any signs of pain or tension when ridden.

Unfortunately, it has become common in some parts of the industry to suppress visible oral behaviours, such as tongue movement, mouth opening, or other signs of discomfort, by tightening nosebands. In the case of a discoloured tongue, this approach not only conceals pain but compounds it, creating a clear and avoidable welfare hazard.

With this in mind, it is not difficult to see how any pressure, whether physical or psychological, can aggravate these risks, increasing the likelihood of pain and tongue discolouration.

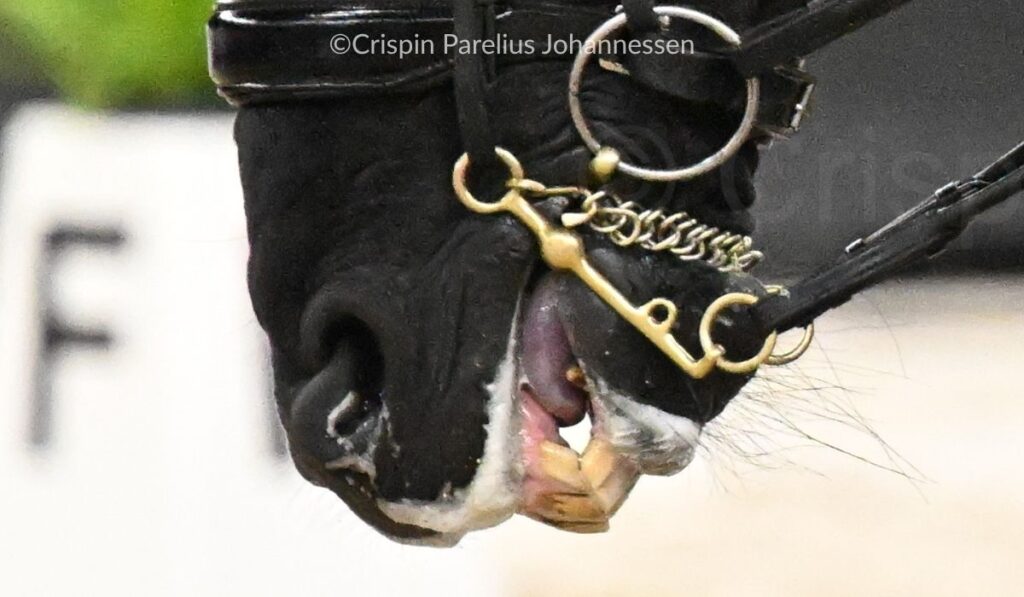

Figure 7. In medical terms, the pattern of circumferential compression and distal discolouration is equivalent to what is known as a ring tourniquet, where pressure applied around a soft structure restricts circulation to the tissue beyond the point of compression – a situation where pressure applied around a soft structure, such as a finger, limb, or in this case the tongue, obstructs circulation to the tissue beyond the point of constriction. The tissue becomes pale, then dark or bluish as carbon dyoxide accumulates in the distal portion of the tongue and oxygen is depleted. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen. Do not reproduce without permission.

Why some horses are more susceptible:

Additional anatomical factors may make some horses more susceptible to blood flow restriction in the tongue than others.

Muscular and vascular constraints

The tongue is connected (via the lingual process) to a small group of bones in the throat called the hyoid apparatus, which is linked to muscles that run down the neck and connect to the shoulder region and the hind end, affecting the entire postural system of the horse. One of these muscles, the omohyoid lies between two major blood vessels, the jugular vein and the carotid artery. If this muscle becomes overdeveloped or contracted (from posture, compensation, or overtraining), it may press on these vessels and restrict blood flow to the tongue, especially when combined with pressure from bits and tight nosebands.

Another muscle, the hyoglossus, helps move the tongue downward. If the bit presses the tongue too hard, or the horse tries to resolve the pressure, this muscle can compress the main artery supplying blood to the tongue.

The double bridle dilemma

These effects vary from horse to horse depending on their conformation and the shape, type and fit of the bit. In double bridles, where two bits are used in a tight space, the risk of overcrowding and compression is much higher.

Figure 8. Relentless pressure, not just moments-in-time. With high-resolution, fast-frame photography it is easy to see how bit pressure combined with a noseband that limits mouth opening and a very short neck aggravates the risks, increasing the likelihood of pain and tongue discolouration. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen. Do not reproduce without permission.

The physiology behind the blue

A blue (or greyish-purple) discolouration of tissue that is normally pink when healthy is a symptom of cyanosis, i.e., a visible sign that the blood in that area is not carrying enough oxygen. This lack of oxygen within the tissue is called hypoxia.

Cyanosis and respiratory failure

Cyanosis can occur when oxygen levels in the blood are too low to supply the tissues adequately. In medical terms, this often relates to two types of respiratory failure, both involving hypoxia.

Type 1 Respiratory Failure:

Blood is not being properly oxygenated, usually due to damage in parts of the lungs. However, carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels remain normal (normocapnia) because CO₂ is more easily exhaled than oxygen is absorbed.

Type 2 Respiratory Failure:

The lungs are not ventilating well enough to eliminate CO₂ (hypercapnia), so both CO₂ and oxygen levels are abnormal. This is a more serious condition that can lead to central nervous system depression, organ damage, and respiratory acidosis. It requires immediate treatment.

Why “too much oxygen” is a myth:

In either of the cases above, cyanosis associated with respiratory failure is considered a medical emergency. Without urgent intervention, typically involving supplemental oxygen and investigation of the underlying cause, it can lead to respiratory distress and death.

Figure 9. High-resolution photographs make it clear that, especially in elite sport horses, tongue discolouration is caused by pressure from the bit(s). Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen, do not reproduce without permission.

Setting the record straight: Misrepresentations of hypoxia

Some commentators have incorrectly claimed that blue discolouration of the tongue in horses may reflect high oxygen levels in the blood. This is physiologically inaccurate.

For example, a statement from a representative of a national equestrian federation compared blue tongues in horses to elite human athletes showing bluish fingertips or lips due to increased oxygen and carbon dioxide circulation. This demonstrates a complete misunderstanding of basic physiology.

In reality:

- Bluish lips or fingertips in humans may indicate peripheral cyanosis, which can sometimes be harmless (e.g. cold exposure), but if persistent, may suggest underlying health problems.

- In no case does hypoxia mean “too much oxygen.” It means too little.

- If an elite athlete had elevated CO₂ levels (as seen in Type 2 respiratory failure), they would not be capable of high-level performance and would require hospitalisation.

To equate blue tongues in dressage horses with normal features of athletic performance is both scientifically unfounded and potentially misleading in welfare discussions. This is not just because hypoxia never represents increased oxygen levels, but because in these cases, the tongues are visibly compressed and deformed by the bits. Nevertheless, let’s discuss cyanosis.

Figure 10. It is not just dressage nor just double bridles. High resolution images reveal that oral tissues are under high levels of compression during jumping events. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen. Do not reproduce without permission.

Types of Cyanosis: Peripheral vs Central

In equine discussions, the distinction is often misunderstood, however, in medicine, cyanosis is classified by where it appears and what causes it:

Peripheral Cyanosis

Peripheral cyanosis affects the extremities, fingers, toes, and sometimes the lips (circumoral cyanosis) but the tongue and mucous membranes are not involved. It is often caused by poor circulation or vasoconstriction (e.g. in cold weather), and while it may reflect chronic disease, it is rarely life-threatening.

Central Cyanosis

Central cyanosis affects the mucous membranes, including the tongue. It reflects a more serious, body-wide lack of oxygen and is typically associated with life-threatening hypoxia. This form of cyanosis demands emergency intervention to restore blood oxygen levels.

Localised hypoxia: The real cause

If a horse is seen competing with a blue or discoloured tongue, it is unlikely to represent true central cyanosis. Many images show the rest of the mucous membranes (gums) appearing normal in colour, and only the distal portion of the tongue, the part extending beyond the mouthpiece, is affected.

Given the level of veterinary oversight in elite sport, it is also reasonable to assume these horses do not have underlying respiratory pathology or systemic hypoxia (e.g., central cyanosis). Such conditions would be inconsistent with high-level performance and would typically present with visible signs of respiratory distress.

What we are observing is localised hypoxia due to mechanical compression—not systemic oxygen deprivation

The central role of equipment

High-resolution photographs make it clear that the discolouration is caused by pressure from the bit(s), and likely worsened by double bridles, tight nosebands and hyperflexed head-neck positions imposed during training and competition.

The portion of the tongue beyond the bit appears to be compressed for long enough to restrict blood flow, consistent with a tourniquet-like effect.

When this compression is maintained, blood flow to the portion of the tongue beyond the bit is partially or completely cut off.

Figure 11. Ergonomic bridles and single mouthpieces do not eliminate the risks. A discoloured tongue in a horse wearing a Micklem bridle with a snaffle bit, taken during an Icelandic Horse event. Image ©Crispin Parelius Johannessen. Do not reproduce without permission.

Bits and bridles as tourniquets

In medical terms, this pattern of circumferential compression and distal discolouration is equivalent to what is known as a ring tourniquet, where pressure applied around a soft structure restricts circulation to the tissue beyond the point of compression – a situation where pressure applied around a soft structure, such as a finger, limb, or in this case the tongue, obstructs circulation to the tissue beyond the point of constriction. The tissue becomes pale, then dark or bluish as oxygen is depleted.

In human medicine, ring tourniquets are rare and usually accidental – caused, for example, by a tight band, dressing, or piece of jewellery. In these horses, however, the same physiological effect is a foreseeable consequence of the interaction between bit design, rein tension, oral anatomy, and restrictive nosebands.

Rein tension and noseband pressure

Rein tension studies show that the forces applied to the bit rise and fall with each stride, however, these changes happen very quickly. A blue tongue reflects the rider’s failure to lighten the contact sufficiently and long enough to restore normal blood flow.

High-speed photographic sequences of elite dressage performances (each capturing nearly 10,000 close-up frames of the horse’s head and mouth and discoloured tongues) confirm that oral tissues are under sustained compression from nosebands, bridoon and curb bits for the duration of the test. This sustained pressure suggests that riders rarely release the contact, possibly because judging conventions discourage visible rein releases and reward continuous “on the bit” tension, a standard that conflicts with what the horse’s physiology needs for comfort and welfare.

Watch the fast-frame, image sequences of an entire Grand Prix dressage test in this presentation.

Between air and pain: The mouth-opening paradox

Horses are obligate nasal breathers, but opening the mouth plays a crucial role in relieving oral pressure, repositioning the tongue, and momentarily restoring comfort. However, this same act can compromise the mechanics of breathing, as opening the mouth breaks the seal and alignment of the upper airway that enables efficient nasal airflow. In other words, the horse’s attempt to relieve oral pain may come at the cost of respiratory efficiency.

When nosebands are tight, the horse loses this limited avenue for self-relief and cannot adjust the tongue or alleviate pressure, further intensifying discomfort.

The resulting combination of oral pain, restricted opportunity to resolve it, and increased effort to breathe may create sensations of air hunger or breathlessness, especially when compounded by a low head–neck angle.

While generalised hypoxia is unlikely during competition, the interplay between posture, airway restriction, and soft-tissue compression adds substantial weight to welfare concerns.

A welfare signal we can’t ignore

When we see a discoloured tongue (i.e., anything other than pink) in a ridden, bitted horse, we are not witnessing a minor cosmetic issue or an incidental anomaly. We are seeing evidence of impaired blood flow and nerve compression in highly sensitive, vascular tissues, most often caused by mechanical compression from equipment. This is particularly relevant in elite sport, where riders are expected to maintain consistent rein contact and demand quick, precise responses to rein aids.

This is very unlikely to be central cyanosis and not a reflection of peak athletic performance. It is localised hypoxia, resulting from bit pressure, restrictive nosebands, and muscular tension, all applied over time.

In many cases, it visually and physiologically resembles what in human medicine is known as a ring tourniquet effect: pressure severe enough to reduce or cut off circulation to soft tissues.

This pressure is not painless. It is not neutral. The notion that there is “no conclusive evidence” of pain ignores decades of clinical understanding from physiology and human medicine, where tourniquets are known to cause immediate and intense pain, followed by predictable tissue damage and neurological consequences if left unaddressed.

In the case of the horse, we are talking about tongue compression, involving tissue innervated by the trigeminal nerve, one of the most pain-sensitive structures in the body.

This is not something that should be tolerated, let alone normalised.

Once identified, it places a clear duty of care on riders, trainers, judges, stewards, and governing bodies. The solution lies not in hiding signs of distress with tighter tack or favourable scoring, but in acknowledging the risk, and removing its cause.

What comes next

In a follow-up article, we will examine what the medical literature tells us about tourniquet pressure, and why it supports the view that tongue discolouration in horses must be treated as a reliable indicator of pain-induced distress. With that knowledge, we can move beyond the debate and begin to take meaningful steps to protect the horse.